The response to the Encor Series 1 has been seismic – in a crowded restomod field, it’s provoked fierce debate across the car world internet in the week since it was revealed.

It’s also been hugely popular – Encor commercial director Simon Lane had a full inbox of enquiries within a matter of hours of the launch. In a week, it’s looking like production is booked out till the end of 2026. At £430,000 plus VAT and a donor car, that’s no small order. As Simon – who has worked for Lotus, Aston Martin and others before Encor – says, a new breed of restomod that foregoes horsepower wars for driving purity is what’s leading the appeal.

“Customers I speak to are bored of the horsepower race,” he says. “Modern cars have 700, 800, 900bhp; by the time you’ve pulled the paddle for third gear, you’re in licence-losing territory. They’re also much heavier now due to electrification and tech. Our aim has been twofold: to create automotive art – something pure and beautiful – and to create a fun, usable road car.”

Encor was conceived by five founders who all knew one another from their time at Lotus. Simon leads the commercial side and Daniel Durrant is design director, while Mike Dickison manages engineering, supply chain and manufacturing – we’ll have further details from the latter later on. The idea for an updated Esprit came about many years ago, but tightening regulations and the realities of type approval made it clear that such a car would be easier to realise outside a major manufacturer.

The Encor project itself started three years ago. “The ‘restomod’ space has grown because it offers freedoms you simply don’t get with new-car homologation,” Simon says. “Pop-up headlamps are a good example; you’d never get them through on a new car now.”

The team were confident the project had legs. “Customer research confirmed strong enthusiasm for the wedge-era Esprit’s return,” he explains. “It’s still fondly remembered as a fantastic driver’s car and a beautiful shape.”

And it’s a team with Esprit lore deep in their bones. At Encor’s Chelmsford base, there are two extremes of the Esprit world – an S1 and a V8 Sport 350, the latter of which belongs to Mike Dickison, who also owns an Series 2 Esprit; Simon also owns a GT3.

“Our aim is to amplify everything that was good about the original and address the shortcomings – particularly by modern standards,” Simon explains. “Mike kindly allowed us to strip his cars so we could digitally scan them and create our own CAD. We’ve done the same with the two donor shells. We now have what is probably the most comprehensive catalogue of Esprit data outside Lotus – possibly more than they have themselves. We’ve learned a huge amount by taking the cars apart, including a few surprises along the way.”

The brand name, Encor, emerged during this early creative process. Its five letters sit neatly where the Lotus badge once did, the union flag integrated into the ‘E’. The cars are built in Chelmsford with UK suppliers wherever possible. “We’re all patriotic Brits, the car is built in Chelmsford, and we’ve used UK suppliers wherever possible. Most major components are UK-sourced,” Simon says. Production will run to 50 examples – the Encor Series 1 announced on the model’s 50th anniversary – and the plan is for Encor to remain a low-volume, specialist manufacturer rather than scale for mass production. “‘Encore’ [with a second ‘e’] also means a second performance – a return to the stage – which is exactly what we’re doing,” Simon adds.

The engineering approach reflects the team’s belief that many modern performance cars have become too heavy and too powerful for real-world enjoyment. “The original Esprit is a joy on the move, but usability is an issue. I drove one yesterday – perfectly restored – and even so, watching the temperature gauge climb while stationary was nerve-wracking; we had to switch it off before something burst. We’ve engineered our car to be genuinely usable,” Simon says.

“It is lightweight – sub-1200kg – which is almost unheard of for a modern road car of this type. Yet it remains comfortable and engaging – we’ve kept key things that made the Esprit special: the steering rack, which we’ve refurbished, because the steering purity is wonderful. Suspension geometry is unchanged, using Sport 350 components. Springs and dampers may be tweaked in testing because our car is so much lighter, but the ride quality will remain true to the original: compliant, not a track-only set-up.”

As for the powertrain, the team chose the Lotus-designed V8 over the four-cylinder turbo – for many Esprit purists, the latter is the more desired option: so why go for the eight-cylinder option? “I owned a four-cylinder turbo Esprit; it’s a great engine, but there’s a ceiling to the power it can reliably make, and we needed more,” Simon explains. “The US is a major market for us, and the V8 was very successful there – roughly half of production went to the States.”

The V8 model was developed during Lotus’ era under General Motors ownership. “A huge amount of investment went into developing that V8 originally, yet it was massively undersold and its true potential was never fully realised,” Simon says. “One criticism at the time was the sound; we’ve addressed that with an almost straight-through exhaust. Modified Esprit V8s can sound fantastic – distinct from both Detroit V8s and British cross-plane units. This is a flat-plane crank, and it will sound superb.”

Early V8s were known for their reliability issues, which Simon puts down to inconsistent build quality when new. “We are rebuilding engines properly, to a high standard, with new technology. We did look at alternative powertrains – Colin Chapman was famously un-precious about where engines came from – but for many good reasons we decided to keep the Lotus V8 and finally realise its full promise,” he explains.

In the week since the car’s reveal there’s been disquiet among UK enthusiasts about sacrificing donor cars. “The V8 is the second-most numerous Esprit derivative, so the supply pool is strong,” Simon explains; around 600 were sold to the US alone. “Many have been neglected; our first two donors looked like they’d lived in the sea and would have required enormous restoration costs. One of those shells will actually save another Esprit – someone needed a replacement shell for his yellow car, and we’ve sold it to him.”

Simon says garage-queen V8s won’t be used for the Encor Series. 1. “Globally there are hundreds of cars, particularly in the US, that are in rough condition,” Simon says. “In fact, several owners with immaculate V8s have said they’ll source a rough one specifically to send to us as a donor.”

The emphasis is on the Encor Series 1 as being a road car, not a track weapon. “Customers at this price point already own GT3 RSs and similar. Our car will sit alongside those – used for specific purposes,” Simon says. “It’s perfect for a long European drive; comfortable, refined and with the tech modern owners expect. We’ve integrated reversing and 360° cameras, Apple CarPlay, keyless entry and vastly improved pop-up headlights. The originals were like two candles – these are proper lights.”

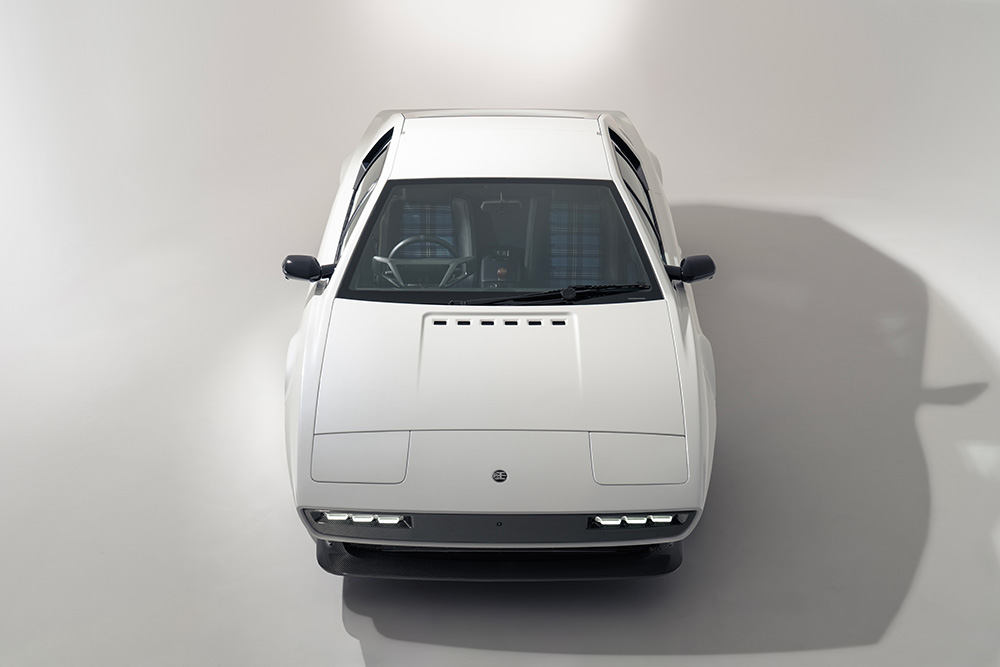

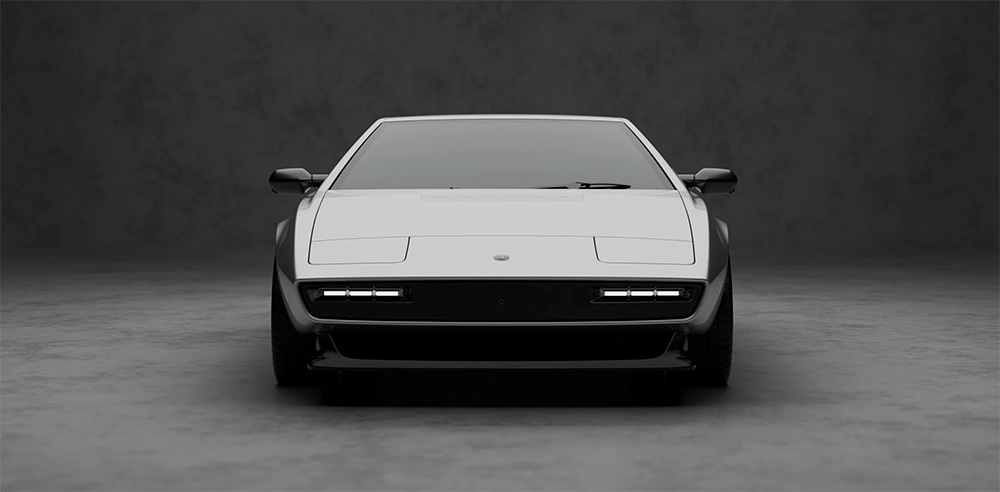

Simon says the overall design has been an exercise in restraint. “Modern OEM design tends to be overloaded with surfaces, wings and aero features,” he muses. “We’ve returned to a very clean, folded-paper wedge – something we haven’t seen in decades. Many of us grew up with wedge-era poster cars, and everything exotic seemed to be a wedge then. Bringing that form back felt right.”

The design

Daniel Durrant has form for Lotus – he spent 14 years at Hethel working on projects such as the Emira and Evija Fittipaldi Edition, among others, and he has worked with AMG and Koenigsegg as well. “The project began with an understanding that we had a responsibility to a very well known and much-loved car,” he says. “Creatively it was unlike almost anything else I have worked on. Normally you begin with a clean sheet and develop shapes and ideas based on the package and whatever feels appropriate at the time. Here the challenge was the opposite – we were dealing with an existing design that already had a strong character. The task was to distil it, refine it and elevate it without losing its essence.”

That distillation process involved bringing the car closer to the original Giugiaro vision. “Manufacturing feasibility, cost and engineering constraints all have an impact and gradually dilute the purity of an original vision. We felt we had the opportunity to reinstate elements of that vision,” Daniel says – so the Morris Marina door handles were an early casualty. “Modern technology allowed us to undo some of the compromises and reveal the clarity that was always there. We never needed to invent a new character for the car – we simply needed to let the original one re-emerge.”

The team studied the early cars closely, noting where limitations in glassfibre construction had introduced visual clutter. “Even the join line down the centre of the body, created because Lotus used GRP mouldings glued together like a boat hull, was a manufacturing necessity rather than a design decision,” Daniel says. “It was ingenious for its time but unnecessary now. Removing it gave us a much purer, more elegant form closer to the original sketches.”

The Encor Series 1 has done away with glassfibre – it is crafted out of carbon, which Daniel says allowed for further improvements. “Carbon is a design cheat code because it enables seamless shapes and large single-piece mouldings impossible in glassfibre,” he adds. “That means greater rigidity, dimensional accuracy and tighter shut lines. We know exactly where every part sits in space, which is essential for features such as flush glazing. It is a very different standard from mass production, where tolerances from front to back can be a major challenge.”

Daniel is particularly proud of the lighting units on the Encor Series 1 – it’s a common area where restomods can fall down. “Many restomods simply bolt on aftermarket units that don’t suit the car. We wanted modern performance without losing the design integrity. The headlights were straightforward: modern projector units are far smaller, so we shrank the housings to avoid the look of a tiny ‘pupil’ in a huge lamp. The pop-ups now open only half as far as the originals yet give far better light and a small aerodynamic gain,” Daniel says. “The daytime running lights and indicators are small modules set in machined-aluminium housings that double as heat sinks. They are functional, integrated and aligned with the geometric form language of the car. Nothing is decorative for its own sake – everything earns its place.”

With a high-performance V8 – and two turbochargers – comes heat management, something the Series 1 Esprit wasn’t known for with less than half the horsepower, half the cylinders and sans two turbos. As such, heat management was a major engineering and design focus for Encor. “The front apron is now completely open to feed the radiators, but we kept the short overhang to preserve the Series 1 proportions,” Daniel says. “A slot at the top of the tailgate acts as a chimney to extract heat, aided by aerodynamic low pressure. The rear diffuser area is also opened up and additional fans support cooling. We know the car will be driven in hot climates, so it had to cope.”

Daniel takes particular delight with the frontal design of the Encor, decluttering the original yet retaining its ethos. “The original had many visual breaks and surface changes, but by bringing everything together the design is cleaner and more elegant. Simplicity is often the hardest thing to achieve,” he says.

Moving alongside the car, the loss of the Marina door handles has been a major win, as has rationalising the tailgate. “The original had multiple frames and trims to cover manufacturing tolerance. Now we have perfect shut gaps and flush heated glazing. The tail-lamps follow the same philosophy: the Series 1 had three distinct shapes because of parts-bin components. We reduced it to one cleaner, quieter graphic.”

The wheels were another challenge – the Series 1 Esprit uses 14in alloy rims which simply wouldn’t be able to handle the Encor Series 1’s power. “With a short wheelbase there is a temptation to go larger to adjust proportions, but we wanted something visually simple with good cooling and authentic character,” Daniel says. “Inspiration came from the Wolfrace slot mag and the Sport 350 lightweight wheel. The five-spoke form echoes the Series 1, and even the direction change in the spokes ties into the body side surfacing. Again, less is more.”

Simplicity was also the name of the game for the interior. “Most substrates are carbon, some left exposed and others trimmed in leather. Screens were avoided in favour of a cleaner, more timeless approach,” he explains. “The philosophy throughout was purity, clarity and respect for the original design, executed with modern precision.”

Of course, the Esprit – particularly the Series 1 – is not known for accommodating taller people. Engineering director Mike Dickison explains that while the interior is exactly the same size as the original, the V8 was already less cramped than the early cars because the Peter Stevens redesign had made an effort to improve packaging.

“We have made certain changes, though. For example, the headlining is trimmed directly onto the roof rather than attached to a separate panel, which avoids lowering it further,” he explains. “That said, exceptionally tall people will still struggle in a standard car. For those customers we can offer a bucket-style seat, essentially a lightweight shell with tailored padding. A good-quality one can be surprisingly comfortable, and it creates more space for the driver.”

Discussions were had about lengthening the cabin or raising the roof, but Mike says that would have compromised the very thing Encor was trying to preserve about the original car. “We could have moved the bulkhead without cutting the chassis, which remains entirely unmodified, but after much deliberation we chose to keep the proportions intact,” he says.

“We have achieved some small gains, though,” Daniel adds. “The carbon tubular structure running down the inside of the A-pillar and into the sill is extremely compact, so your head position sits a few millimetres further outboard. The tuned roof structure lifts headroom by a few millimetres, and the side structure sits slightly further outward, too. These are small improvements, but they do help.”

The engineering

“When you look at an old Esprit, it is easy to think it is in good condition because the panels still look tidy. The reality only becomes clear once the car is on a lift,” chuckles Mike Dickison. As mentioned earlier, he owns two Esprits, an S2 and a Sport 350, but he has also led engineering roles at MIRA, Tickford and C2P.

“A specialist who regularly carries out full ground-up rebuilds told me that you should budget somewhere between £100,000 and £130,000 simply to bring a standard V8 back to the condition it should be in. Most are now around 25 years old, and they all need suspension, dampers, springs, joints and bushes. They were assembled dry originally, as most cars were, so you cannot simply undo the bolts. You end up sawing through many of them, which is very labour intensive. Some owners may insist their car is excellent, and it may have a retrimmed interior and fresh paint, but underneath most are far from perfect. There will always be a few exceptions that have been cherished from new, but the majority are rather tired.”

As such, the Esprit V8s being used as donor cars may look good, but they often require work. “The early steel chassis is thin and unprotected in places, and both of the cars we inspected were completely red with rust underneath. Every pipe was corroded,” Mike says. “There is also a known rust trap at the front of the chassis. Because it is folded sheet metal, it forms a shallow tray that collects debris. The V8 cars were galvanised, which prevents total corrosion, but the front and rear sections suffer from heat and road grime. On our cars the galvanising had degraded into a black crust, which came away during blasting. It had sacrificed itself to protect the steel, which is what galvanising is supposed to do. We have caught them just in time. The chassis are still structurally sound and need no welding, but leave them a few more years and they would start to rot.”

Mike says Encor blasts only the areas that need it – he says the centre tunnel is always fine because it is protected by the body, but the front and rear require attention. “We then epoxy coat and finish them in a two-stage paint system,” he says. “The result is not only far better protected but visually superior to the original finish, which always looked rather utilitarian.

Encor uses trusted suppliers for the engine and transmission, specialists with long histories with Esprit V8s, and both units are stripped down to the last nut and bolt, while the casings then go to another specialist for vapour blasting and cleaning.

“The process depends on the material, because steel or iron is treated differently from aluminium; once cleaned, the parts are masked and coated. The transmission casing, for example, receives a high-temperature ceramic coating rather than ordinary paint,” Mike says. “The engine specialist inspects every internal part, anything even slightly worn is replaced. On one of the two engines we have completed so far we fitted a new block and crankshaft – the original parts could have been repaired, but we are not reconditioning engines, we are effectively remanufacturing them. Fortunately our specialist holds a large stock of factory spares. Every stud, every fatigue-sensitive component, every actuator and every sensor is replaced. The result is essentially a new engine.”

Mike says the process goes beyond that, addressing any shortfall in the original design. “The V8 didn’t have many; early engines suffered from coolant leakage due to incorrect sealant, but that was sorted very early on. Our specialist knows the issue well; it has rebuilt more Lotus V8 engines than anyone else in the country,” he says.

The pistons are replaced with higher-grade forged units, and original injectors are replaced with modern, high-capacity items. “The ECU is changed because we have moved to an electronic throttle body. Updating the electronics allows much finer calibration of fuelling, emissions and throttle response compared with the 1996-era system. We are working with another specialist, a former Lotus engineer, who now develops upgraded ECUs for Lotus models right up to modern cars. This lifts the quality, performance and drivability of the engine.”

Beyond those changes the engine is largely original; the turbochargers are difficult to replace due to the tight packaging within the chassis, so the team has improved what they can. “The impellers are now billet-machined items, the bearings are replaced and we fit a higher-performance wastegate, all supplied by another specialist,” he says. “The turbochargers on road engines rarely use roller bearings, and we were advised not to fit them because they will not last. The original twin-turbo layout has minimal lag anyway, thanks to the Esprit’s light weight and the relatively small turbochargers. The new system will be better again, particularly as we have reduced the car’s mass by around 200kg and increased power and torque. We quote 0-60mph in around four seconds, which is deliberately conservative.”

The intercoolers have been removed, which drops power to around 400bhp. “We are not chasing extreme figures – there is only so much power you can put through the rear tyres. However, we are working on a potential charge-cooling solution with a specialist cooling manufacturer, and we may adopt that once the main development programme is complete,” Mike says.

The cooling system has been redesigned, with uprated radiators, oil coolers and fans. Boost pressure remains modest at around 0.9 bar. “You can push these engines much harder, but reliability would suffer and the gearbox casing would become a weak point.”

Encor has chosen to retain the original gearbox – something that might cause an eyebrow to raise given that it was the part of the V8 models that held the car back – between 500bhp and 650bhp was possible, but drivetrain issues meant it was pegged back to 350bhp.

“We initially looked at modern alternatives such as Getrag units used in Porsche applications. They offer decent torque capacity, but availability was uncertain and the ratings are conservative. Getrag now sells only remanufactured units and supply cannot be guaranteed – and while the packaging was possible, it was not ideal,” Mike says. “We also investigated the Quaife unit used in GT40-type applications, which is extremely strong but simply would not fit within the Esprit’s tight chassis rails.”

Quaife does, however, offer an internal conversion for the original Renault-derived box. “It replaces the two-piece mainshaft with a one-piece shaft, and changes multiple gears and ancillaries – Lotus itself used similar upgrades on the Sport 350 after suffering failures,” Mike says. “It is expensive but proven, and because it retains the original casing we avoid new mountings, new driveshafts and a long development programme. For a run of 50 cars it is the most sensible route. We also fit a torque-biasing differential; again the aim is sensible, reliable performance, not headline figures.”

The Encor Series 1 suspension follows a similar philosophy. “The Esprit V8 drives wonderfully as standard, and the Sport 350 adds a slightly firmer edge without compromising its character,” Mike says. “Tastes have changed and modern cars tend to be firmer, so we believe a Sport 350-style set-up suits the ethos. However our carbon structure is significantly stiffer and lighter, so we may adjust spring rates once we have driven the development car. Bilstein dampers developed with Lotus are used, and geometry follows Lotus factory settings. If needed we can commission custom springs to fine-tune the balance.”

On the structure, the original Esprit used a plywood bulkhead acting as a shear panel – and it was still used during the V8 era. “Plywood works but is not ideal for a modern overhaul – we have replaced it with a double-skinned, foam-filled carbonfibre bulkhead that is far stiffer and extends deeper into the engine bay,” Mike says. “The A-pillars and cant rails are now closed-section carbonfibre structures, effectively forming an integrated roll cage. The sills have been redesigned as larger two-box sections with varied carbon thickness depending on location, significantly increasing stiffness. Carbon also brings crash-safety benefits – the original Esprit was already good in this respect and the new structure improves it further.”

Mike says the Encor wheel and tyre philosophy follows the same logic. “If nothing is wrong with the original approach, do not change it – so we use the nearest modern equivalent to the V8 Esprit sizes,” Mike says. “Wider Series 1 tyres would be inadequate for the torque, while exact original sizes are no longer available in modern compounds. Offsets are kept the same because steering feel is highly sensitive to them. The front tyres are slightly wider, only because original sizes are obsolete. Tyre technology has improved hugely in the past 20 years, so modern tyres deliver significantly better performance even if the sizes differ slightly.”

The electronics and electrical system are entirely new, built around architecture developed for other customer projects. “One of the first things you’d want to replace on any 20-year-old car is the wiring – particularly the engine harness. These are exposed to heat and age, and on both donor cars we dismantled, the engine looms were in very poor condition,” Mike explains. “All the wiring is therefore new, and the car now runs a modern CANbus electrical architecture that bears no resemblance to the original Esprit’s system. We’ve also adopted digital screens, although they visually reference the original analogue dials. Retaining the old instruments – and the associated tangle of wiring – simply wasn’t appropriate for what we’re building, so we’ve moved to a fully modern set-up.”

Looking to the future

The first Encor is about to embark on an OEM-level test programme. “The second car is in build; once the body shell arrives, it will be built by the end of January. We’ll do six months of testing: hot and cold weather, performance and durability,” Simon Lane says. “Maximum capacity for the factory is three cars built at any one time. Once scaled up, we expect one car leaving every couple of weeks. So there will be fewer in 2026 than 2027. We plan to hand over the first customer car in April 2026 and initially, production will be one a month, scaling up to two, then three per month.”

Encor now has either deposits or allocations for every car it is building through to the end of 2026. “Since the launch on Friday, we’ve had almost 200 inquiries from the website, from as far afield as Australia, Japan, Malaysia, Taiwan and California,” Simon says; he sees no problems with getting the cars across the globe. “Some countries are more straightforward than others, but we approached this with experience. The UK is simple: we haven’t changed the chassis, engine number or gearbox number. Effectively, it’s a restoration, and it’s fine. Most US states are similar. For states with CARB compliance, we’re confident the car will pass the biannual smog test,” he says.

“In countries such as Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark, we’ve already engaged with local authorities and understand the process. For new countries, we’ll research the rules. The key is that the customer owns the car in their country. We can then bring it in under import protection, like sending a classic car for service or restoration without taxes or duties. We keep the chassis and numbers intact, making compliance straightforward.”

For servicing and support, Encor has appointed strategic partners; for instance, the firm is using MyGarage in Europe. “We aim to have three hubs globally to support customers in-region, including the US and Middle East, but the car is designed so it can be serviced at any Lotus main agent willing to work on a modified Esprit or any Lotus specialist,” Simon says. “Wear-and-tear items such as tyres and brakes are standard, off-the-shelf parts and any bespoke parts, such as body panels, will be stocked. The car comes with a 12-month, unlimited-mileage warranty, and support can be provided by local agents or via ‘flying spanners’, sent out as needed.”

The big question, and one every journalist has apparently asked, is what comes next for Encor. Simon’s tight-lipped on the specifics. “We have a ten-year plan – we love Lotus and the Esprit, and we hope to do more in the future.”

More information about Encor can be found here.