Words: Nathan Chadwick | Photos: ACO/Artcurial and Kevin van Campenhout

“We were very much the little amateur team, the sideshow,” says Tiff Needell of the Alpha Racing Team Porsche 962, chassis no. 154, his steed for the 1990 All Japan Sports Prototype Championship. “Japan was very competitive – Nissan and Toyota were going head-to-head at the front, and there were some front-running Porsche teams that had been competing in Japan for five or six years; the 962 was at the end of its days, so it was never going to be a winner.”

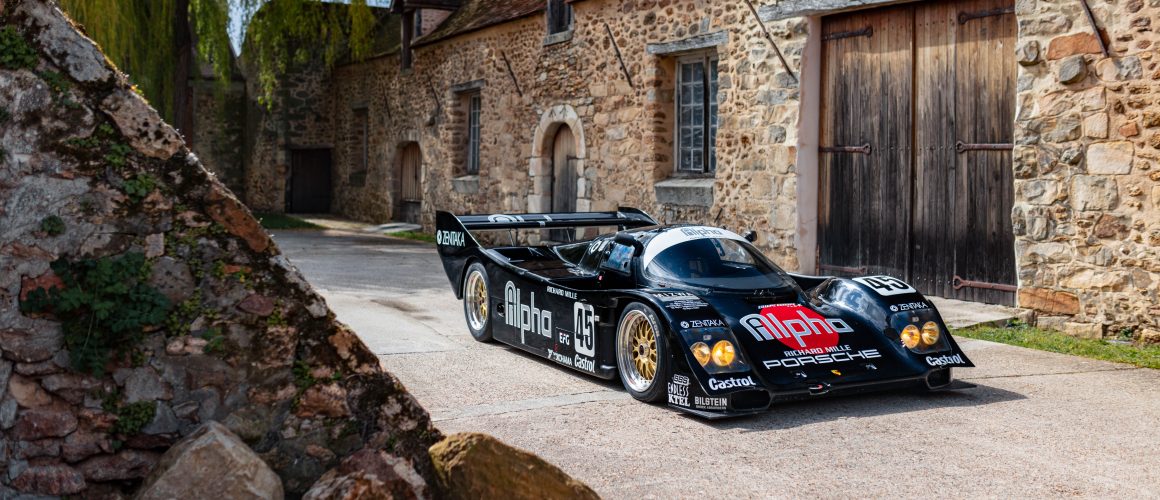

Indeed it wasn’t – but chassis 154 would defy all the odds and finish third at Le Mans that year, the last La Sarthe podium for a 962 (discounting 1994’s Dauer), beating not only its Japanese rivals, but the much-fancied Joest-Porsche 962s. The car is now due to be put up for auction at Artcurial’s Le Mans Classic sale on June 30, 2023.

For Tiff, the call to go to Japan had come out of the blue from an Irish driver manager, David Kennedy, off the back of a year in a Richard Lloyd Racing-prepared 962 with Derek Bell. For the first couple of races, Tiff was paired with Costas Los. “I don’t think it was his sort of car, with the turbo,” Tiff remembers. “So he was dropped, and I enlisted two Tiff-like Brits, whose racing careers had been like mine, who hadn’t had the really big chances, but I knew they were good drivers: Anthony Reid and Derek Bell.”

“By 1990 the 962 was really out of date, but I was still honoured to drive in Japan, because I’d never really done it apart from the one World Championship race per year,” recalls Derek. “But it wasn’t quick enough.”

There was an ace up the team’s sleeve, however, in the form of team manager Gary Cummings. “He was an American mechanic who’d worked on Porsches for years, and met the Alpha Racing Team’s owner, a property developer, when he’d sponsored a car in the World Sportscar Championship in 1989,” Tiff says. “He virtually built the car on his own in about two months in Japan. He was an ex-military man with a huge booming voice, andhe drilled the Japanese team members in the art of pitstops.”

Derek’s first race for the team, the Fuji 1000km, was cut short by heavy rain, and the second was a round of the World Sports Prototype Championship at Suzuka, which resulted with a creditable eighth-place finish. Then came Le Mans, and chassis 154’s golden moment – one that didn’t involve Derek. He’d be drafted into the two-car Joest team, while the Alpha Racing Team’s drivers consisted of Tiff, Anthony and David Sears.

It was the first year Le Mans would be run with chicanes on the Mulsanne Straight; Porsche insisted its teams run a long-tail, low-downforce wing, which upset many of the private teams. “All the teams had to spend £50,000 on the long-tail set-up, with a new nose and a low-downforce rear wing, and I thought – do we really need this?” Tiff remembers. “I compared the new Mulsanne to the old Fuji Speedway circuit – the length of that straight was equal to the three parts before each braking point, so I thought – is it really low downforce or is it really high downforce? We tried it with the full high-downforce wing, and it was about 4mph slower [down the straight], but the lap time was the same.”

Derek was less convinced. “If Norbert Singer set up a car in a certain way, then it was probably the right way,” he says. “We’d seen other teams change the bodywork and seen some cars fly off the road because they were trying different aerodynamics.”

That’s not to say Singer wasn’t open to discussion. “With most engineers, you can’t talk to them – they only want to be told what they want to hear,” Derek says. “Norbert wasn’t like that, it was just a different atmosphere. He was wonderful, and we had a close relationship.”

Derek actually tried the short-tail car at Le Mans, and it didn’t go well. “I said to Norbert that we spend so much time coming back to those twisty corners that if I had the shorter body on the sprint car, I could go faster. He told me to have a go,” he remembers. “On the second lap, coming out of Tertre Rouge, I was screaming along and suddenly there was a God almighty bang – the whole underside of the car got sucked off.”

Derek trailed around to the pits and went straight into the back of the paddock. “Norbert came up, and he said, ‘it didn’t work, did it?’,” he laughs. “It does provide context on why Porsche was so insistent.”

Undeterred, Tiff enlisted Gordon Horn to build a bespoke carbonfibre wing for chassis 154. “It was easier to drive, nice through all the Porsche Curves,” he says. “Of course, we were still a tiny team – we had our one engine for qualifying and the race. Brun would go out with the spare engine, run high boost and qualify miles ahead of us.”

Keeping fit and focused was also a challenge. “We were just normal journeymen racing drivers, with no trainers or physios,” Tiff says. “We were used to doing single stints in the day and double stints when it was cooler, but we ended up single-stinting the whole race because we were knackered by the end of double stints – it also took us longer to recover.”

A consistently strong, untroubled performance quickly saw the Alpha Racing 962 climb the leaderboard. “The only problem we had was a stone chip in the windscreen, and Anthony got a bit of glass in his eye,” Tiff says.

However, the addition of the chicanes made the race much harder for the drivers. “I used to love the Mulsanne Straight – I was good on the straight. I could relax for three or four miles, until the kink came up,” he laughs. “The chicanes made it much more physical, because we had more downforce. The Porsche Curves were also much faster than they had been before, too.”

The team found themselves running fourth with 15 minutes to go – but then, disaster for the Brun Porsche. “I think the Brun parked just before the corner when I came around to wave at the crew,” Tiff says. “There was a panic on the pitwall, which I didn’t really understand. When I came around for another lap, I saw P3. That was an emotional moment.”

After the flag fell, the mood within Porsche was somewhat sombre. “I remember they took us into the Porsche hospitality tent to congratulate us through bitter teeth,” Tiff laughs. “We’d run our high-downforce cars and beat their ‘factory’ cars – so we enjoyed that. We were so tired; I’m sure I had about two glasses of wine and was drunk in about two seconds after being dehydrated for 24 hours.”

Derek would finish fourth, two laps down on the Alpha car. “That was a lovely, ironic twist,” laughs Tiff. “He left our little Japanese team to go back to the factory squad, and we beat them to the finish.”

Derek would return to the Alpha team for the rest of the Japanese season – but any hopes that the Le Mans result would signal a change in fortunes were short lived. The high point was fifth at the Fuji 500 miles; eighth next time out at Suzuka was the last time the car would see the chequered flag. At Sugo the engine would fail, and at the final race at Fuji, Anthony would collide with a competitor – something that had been on the cards for some time, according to Derek.

“Anthony had this thing about going right up into the apex on the brakes, then hit [the throttle] mega hard again,” he remembers. “He got by a lot of people going into the corner, but I always used to tell him that left no room for error. I was more old-fashioned – brake in as straight a line as possible, get off the brakes, get the car back on its level, turn, and then get on the power. It seemed to work in my career – yet I couldn’t get away from the fact Anthony was electrifyingly fast. But he didn’t really know why he was so fast – it was because he didn’t know when he was about to go off!”

Tiff and Derek would commute to Japan, rather than stay out there for the entire season. “It was pretty brutal for jet lag – we didn’t have horizontal airline seats in those days,” laughs Tiff. “We’d fly to Anchorage, stay over and then head to Japan in the cheapest seats we could get, saving a bit of income. We’d land on Wednesday and then travel to the circuit on the Thursday, then be in the pits for four days and travel home on the Monday.”

For Derek the commute was even harder, as he was living and racing in the US at the time. “Most of it was from the States, and that was a so-and-so because I had to fly from Miami up to Oregon, then get an Italian flight from Portland to Tokyo – it was a hell of a long journey,” he remembers. “You had to get over amazing jet lag and time change, maybe half a day, and you couldn’t do anything enjoyable while getting over it.”

The culture around racing also took some getting used to. “I cannot compare it to anywhere else in the world – it was a totally different culture,” remembers Derek. “The fans were very polite and much quieter, they didn’t come in their thousands into the paddock – they were kept back across the track in their seats.

“I’ll never forget the first time I went out there for the Fuji 1000km with Porsche in the early 1980s. They flew us into the circuit with helicopters from the hotel, ten miles away. We got there for 9.30am and it was totally quiet. The race was starting at 2pm, so we had a warm-up. I remember strolling around and everybody was chatting away, but in the pit it was quiet – no noise, no engines. Then I walked out to the other side and the grandstands were full of people, but they weren’t making a sound – it was uncanny.”

While Derek found the language barrier challenging, Tiff remembers that same issue spurring a great rapport with the other European drivers racing out there at the time. “At one point we had 13 drivers staying in the President Hotel, and we’d all go out and have a lot of fun,” smiles Tiff. “I always remember the six-hour races at Fuji; if you were the first to retire, you’d head to one of the regular clubs in Tokyo at around 10pm. You’d wait a while with a drink, and then someone you knew would turn up halfway through the race. Gradually the party would grow, until 1am when the winners would arrive.”

Despite the Porsche being off the pace, both Derek and Tiff have fond memories of Japan. “The cars were well prepared and some pretty damn good driving went on out there, but we weren’t that competitive and there was nothing we could do about it,” Derek says. “The gentleman who owned the team was not a gung-ho leader, he was more behind the scenes. Tiff steered the team because he knew much more about what they should be doing; I enjoyed driving with Tiff and I enjoyed Japan.”

“It was frustrating against all the factory Toyotas, Nissans and quicker Porsches – it was always a bit of a struggle,” admits Tiff. “But the whole experience was so wonderful – I loved Japan so much. It was such a different culture, but it felt like a second home.”

The car is due to be auctioned by Artcurial at its Le Mans Classic sale on June 30. More details are available here.