Every car-loving child of the 1980s knows the Ferrari Testarossa was automotive pin-up royalty. Along with the Lamborghini Countach 5000 QV and the Porsche 959, it was responsible for more Blu Tack wall stains than even Farrah Fawcett… probably. Fantastically fast, muscular and impossibly wide, the Testarossa was pure Italian stallion in a time when that phrase was [regrettably] popular. Forty years have passed since the Ferrari first landed, and it’s a moment worth celebrating. But to understand how it came to be requires a look at what came before.

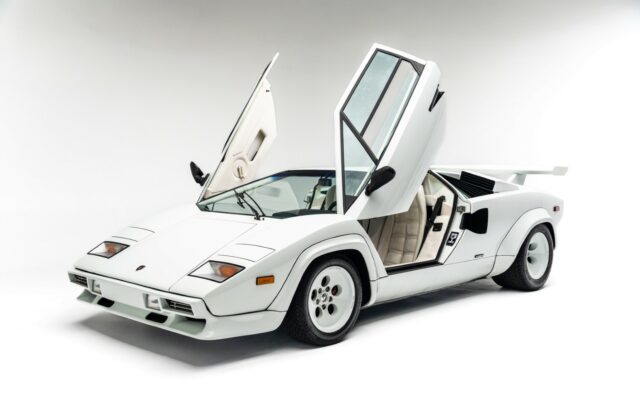

Brigitte Bardot’s reign as the international sex symbol of the 1950s and ’60s was coming to an end right about the time of a step-change in the world of car design. A trio of Italians – Giugiaro, Gandini and Fioravanti, born within months of each other and all in their late 20s – were redefining how cars looked. In just a few years, Lamborghini had swapped the coke-bottle Miura for the origami Countach. Arch-rival Ferrari, too, had an appetite for change.

It’s a given, though, that while Enzo was around, the rationale behind new road car decisions would, almost without exception, be driven by the results of Scuderia Ferrari, the brand’s racing arm. So when the Prancing Horse replaced its front-engined 365 GTB/4 ‘Daytona’ with the mid-engined 365 GT4 BB, it was in response, albeit a delayed one, to the marque’s front-engined racers losing out to mid-engined opposition.

Revealed at the 1971 Turin Motor Show, the BB (for Berlinetta Boxer, according to Maranello) was the first Ferrari-badged road car to feature an engine mounted behind the driver. Earlier 206 GT and 246 GT and GTS models wore Dino badges. Although branded a ‘boxer’, and flat in layout, the twin-cam powerplant was in fact a 180º V12. Bearing the internal code F102A, it had a swept volume of 4390cc. Launched in production form in 1973, right at the start of the oil crisis, initial sales of the BB were understandably slow. Come 1976, though, demand had increased, and Ferrari seized the opportunity to debut a much improved, more snappily named successor: the 512 BB.

Visual changes hinted strongly at ‘fixes’, in the shape of exhaust-cooling NACA ducts ahead of the rear wheelarches; a new, heavily louvred engine cover, and the addition of a chin spoiler up front. Ferrari also addressed criticism of the 365 GT4 BB’s peaky power delivery by fitting a new version of the flat-12 (F102B). An increase in capacity of more than half a litre, to 4943cc, allowed the motor to deliver similar power at lower revolutions, while the added torque improved driveability. Ferrari continued to develop the engine, leading to the introduction of fuel injection for the 512 BBi model launched in 1981.

Despite all the engineering revisions, two major issues had not been solved: the car did not meet the safety and emissions regulations of the increasingly important US market, and its inherent heating problem was never satisfactorily overcome. So, by 1984, the world was ready for a new BB. What it got was an absolute sensation. No longer named Berlinetta Boxer, it instead revived a glorious name from its past, one that made direct reference to the Italian Racing Red paintwork of its cam covers – Testarossa.

Ferrari’s new flagship was launched in Paris on October 2, 1984. Who could forget the iconic publicity shot of the car parked sideways in the middle of the Champs-Élysées? The launch itself was held inside Paris’s Lido, where, once the lights had been turned off, the car appeared from on high on a giant platform as the only lit object in the room. A new Ferrari is always an event, but seeing this one emerge from the relative darkness for the first time must have been unreal.

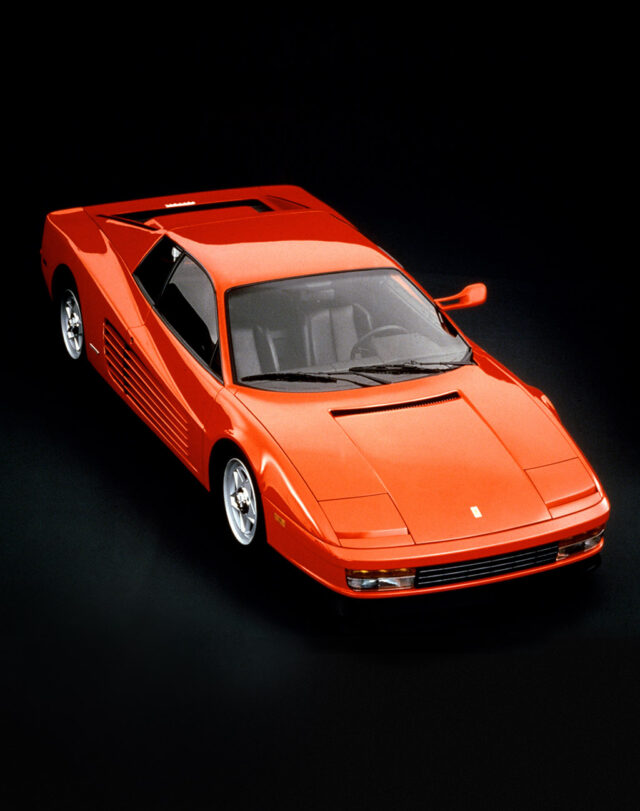

The following day, the Testarossa took pride of place on the Ferrari stand at the Paris Motor Show. Owners and fans of the Boxer series cars were no doubt pleased that, in essence at least, the concept had not changed much. It was still a low-slung, Pininfarina-designed, two-seater Berlinetta powered by a flat-12 motor mounted directly behind the driver. Visually, though, the car represented significant shifts in style from the sharp-nosed ’70s wedge profile of its predecessor to a more substantial silhouette – it had ‘filled out’ in every aspect.

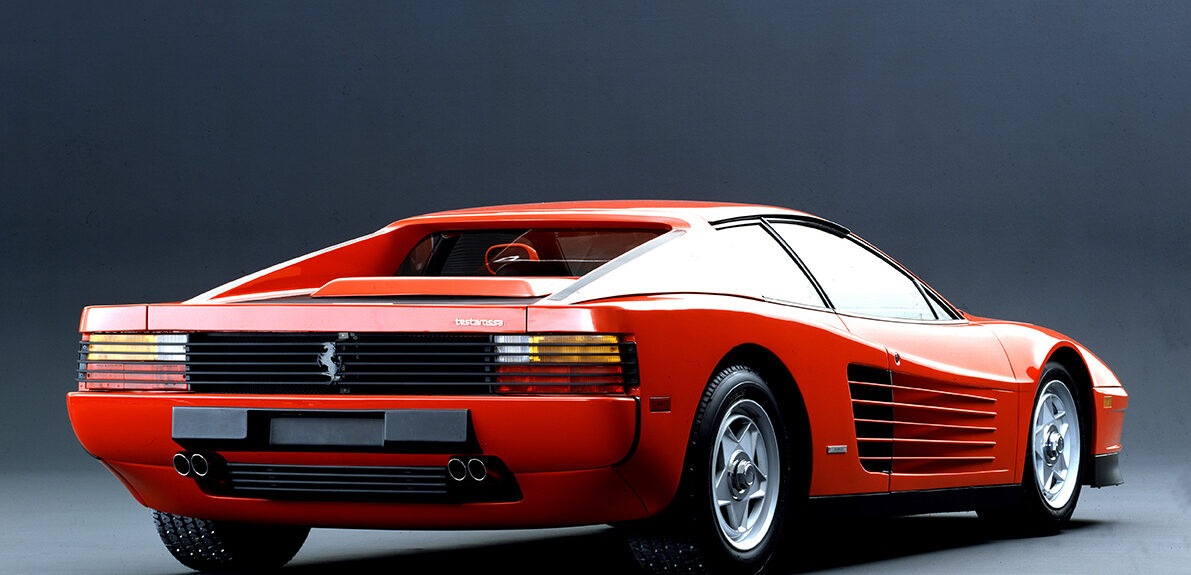

Up front, the Testarossa presented a rounder, far deeper, lift-reducing chin, while at the rear, full-width horizontal slats sat in front of rectangular (gasp!) tail-light units. This was already a huge departure for Ferrari, but the award for the most distinctive new styling feature went to the deep side strakes that started close to the leading edge of the doors, and swelled outwards before blending into dramatically wide rear wings. How wide? 1976mm – nearly 150mm broader than the 512 BB.

The reason for the car’s increased girth was a result of an engineering decision to double the radiator count, as well as to move the entire cooling system from the front of the car to new positions either side of the engine. This was done to ensure the Testarossa met one of its most crucial engineering targets, which was to eliminate the heating problems that had plagued its predecessor. Further benefits of repositioning the radiators, besides cooling the engine more efficiently, were to avoid hot-water lines passing beneath the cockpit, and so inadvertently heating it, to boost the aerodynamics, and to increase the front boot space.

Design work on the exterior styling of the Testarossa was overseen by Leonardo Fioravanti, who’d already been responsible for a string of great Ferraris including the Daytona and BB. Fioravanti’s design team was composed of Ian Cameron, Guido Campoli, Diego Ottina and Emmanuele Nicosia, whose initial concept was chosen for development. The final car was a triumph: not traditionally beautiful – few cars of the 1980s could claim to be that – but rather as a beguiling mix of Wall Street excess, European race-car pedigree and fair degree of Italian glamour.

Apparently, the Testarossa’s signature side strakes were only added to appease those markets where massive inlet openings were outlawed. Although the strakes also appeared as far less prominent details on the subsequent 348 and Mondial models, they were never destined to become permanent fixtures in the Ferrari design landscape. Also quickly discarded was the strange decision to fit just a single side mirror, mounted high up on the A-pillar. A revised model wearing two low-mounted mirrors was shown at Geneva in 1986. Another design oddity was the asymmetric inlet in the lower front spoiler. This distinctive feature directed cool air towards the air-conditioning unit’s condenser.

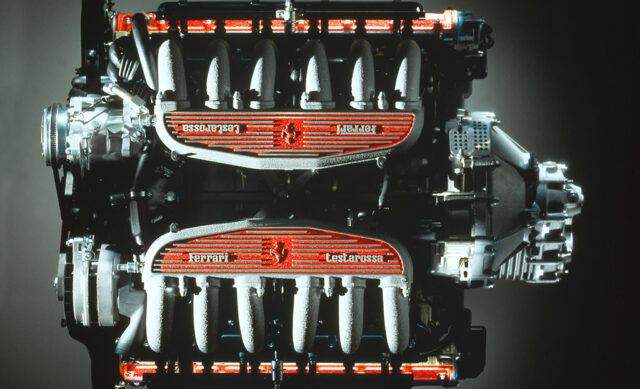

Further areas targeted for improvement over the outgoing 512 BBi included ensuring that the newcomer met all US market regulations, displayed demonstrably better driveability, handling, traction and grip, and delivered more power. To that end, the Testarossa was fitted with a “completely redesigned” development of the 180º V12, the F113A. While the cubic capacity remained unchanged, at 4943cc, the motor now featured four valves per cylinder, ran cleaner, and produced 385bhp at 6300rpm and 362lb ft of torque at 4500rpm.

Incorporating a few elements from the Formula 1 team’s notebook, it made use of a light alloy block and cylinder heads, steel for the inlet valves, Nimonic steel for the exhaust valves, and a Nikasil coating for the pistons and aluminium cylinder liners. Valve timing was driven via cogged Goodyear belts, while Bosch’s K-Jetronic system managed fuel injection. Despite the increase in complexity, overall engine mass was down by more than 20kg, a fine reward for the efforts of the Engine Department overseen by Nicola Materazzi.

A system of two scavenge pumps, one pressure pump and an oil reservoir provided lubrication for the dry-sump engine, which, as before, was mounted longitudinally in unit with a five-speed transmission. A one-inch-larger dual-plate clutch handled the additional power and torque.

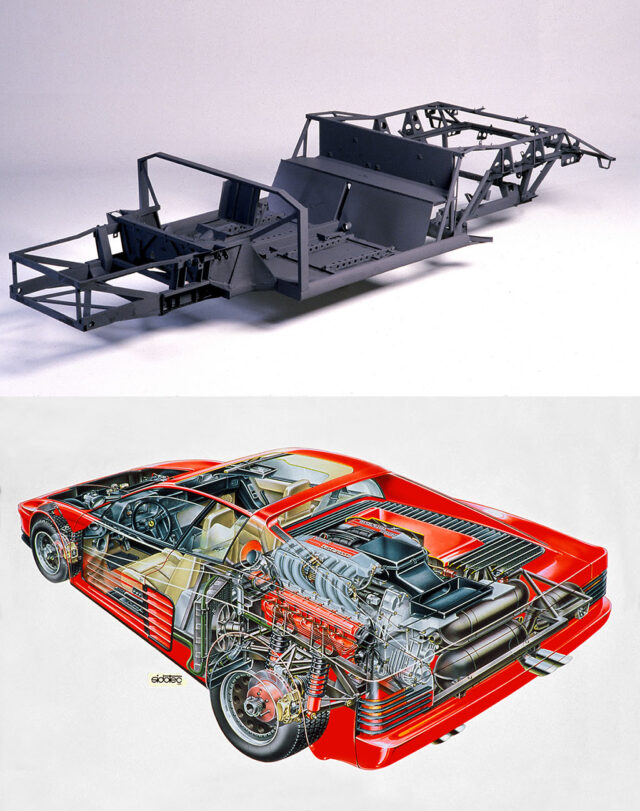

A tubular-steel chassis, suspended via double unequal-length wishbones, coil springs, telescopic dampers and anti-roll bars all around, incorporated a detachable subframe for the engine. Although unassisted, reasonably quick-geared rack-and-pinion steering offered what Ferrari called “great manoeuvrability”, despite running on wide-for-the-time 225 (front) and 255 (rear) VR16 Goodyear rubber. A set of even wider Michelins was also available. Ventilated disc brakes – with four-pot calipers – on all four wheels provided sufficient stopping power. Forty years ago, 0-60mph in 5.2 seconds was definitely what you’d call “exciting”, as was the 181mph top speed.

Described as “a 300km/h living room”, the Testarossa’s leather-lined cabin offered a perfectly judged mix of sporty elegance and comfort. This was one very fast Gran Turismo that was always meant to be driven long distances. Both the seats and the steering wheel could be adjusted, while the compact drivetrain allowed additional luggage space behind the occupants. The list of comfort features comprised air-conditioning, radio, powered windows, central locking and electric operation of that early, strange, single side mirror.

The Testarossa captured imagination like few other cars of its time, perfectly at ease as an icon of popular culture thanks to starring roles in countless films, music videos, computer games and TV shows. By the time the heavily revised 512 TR arrived, Ferrari had shifted almost 7200 Red Heads, making the model by far the most desirable supercar of its era. The numbers don’t lie. Ironically, that ubiquity meant it has taken nearly four decades for the car’s value in classic terms to be properly appreciated. Not before time, we say.