WORDS: JONATHoN BURFORD | PHOTOS: TAG HEUER/RM SOTHEBY’S

Excerpt taken from Magneto issue 9, back issues available on our online store

You require only a passing interest in watches or horology to know that the 2010s have been the decade of the steel sport watch, both vintage and modern. Led by the Patek Philippe Nautilus, Audemars Piguet Royal Oak and any number from the Rolex catalogue, demand and limited supply have resulted in eye-popping appreciation.

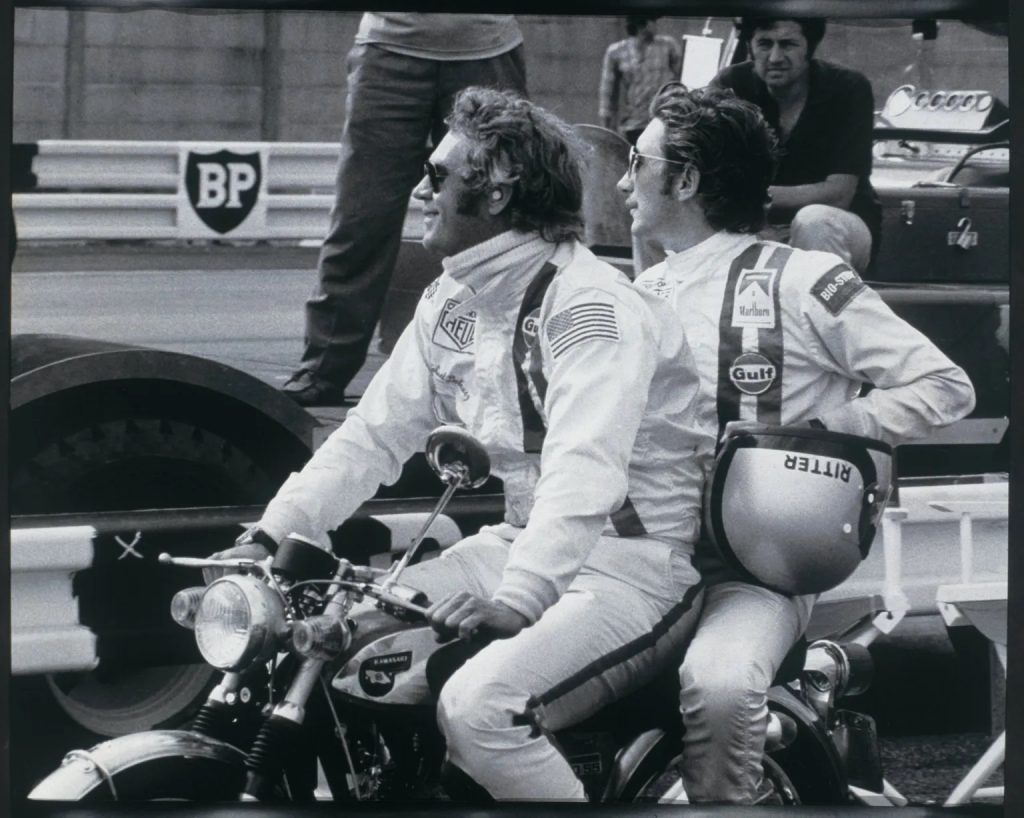

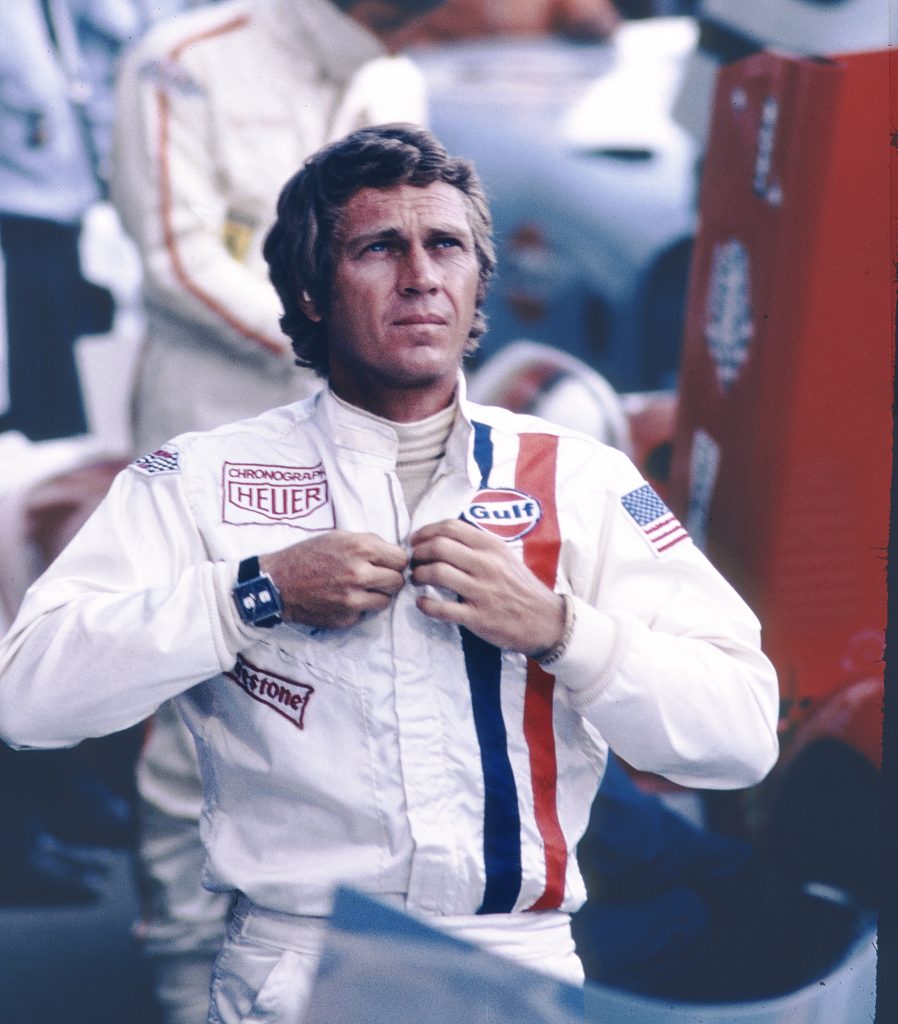

These timepieces’ ‘beach-to boardroom’ flexibility, robustness, understatedness and propensity to develop character and beauty with age – combined with the entry into the market of a large number of collectors who grew up idolising previous wearers such as Steve McQueen and Paul Newman – go some way to explaining this boom. As such, many are now unobtainable to your average collector – and with early A-Series Royal Oaks and Ref 3700 Nautiluses consistently exceeding $100,000 at auction, collectors look elsewhere for value.

This has led to increased interest, scholarship and demand for what were considered lesser brands, such as Heuer, Universal Genève, Gallet and Zenith. Of these, Heuer has had the most interesting few years, highlighted by significant sales from the Arno Haslinger collection in London in 2010, to a market peak around 2017 and market correction in 2018-19, to the 2020 sale of one of the eight Heuer Monacos worn by McQueen during the filming of Le Mans for in excess of $2 million.

Heuer has existed since 1860, making many timing instruments including pocket watches and dash timers. Yet it is the post-war Jack Heuer-era watches, predominantly steel chronographs, that have driven the brand’s popularity. The Autavia and Carrera are often the most headline grabbing and numerous, but it is the unique-looking Monaco – the square, waterproof, automatic chronograph – that I find the most interesting.

Heuer and Breitling both announced the development of the automatic chronograph in March 1969. The two brands had teamed up with Hamilton to develop the Chronomatic (Calibre 11) movement, beating Zenith with its El Primero and Seiko’s Ref 6139 to the punch by a matter of months. These early examples, boasting the ‘Chronomatic’ text on the dial, left-sided crown and midnight-blue dial, are some of the most rare, collectable and desirable Monacos. Later versions read ‘Automatic Chronograph’ instead.

Over time, multiple variants were developed using Calibres 12, 13, 14 and 15, offering a small running second hand and GMT among other functions. A manual Valjoux-powered version arrived in 1974, with the crown now on the conventional right side of the case.

When looking at early Monacos, as with all watches from this era, the basic principles to adhere to remain condition, originality and rarity. Which characteristics trump the others depends on your collecting style, but here are some things to look for. Monaco cases are a combination of brushed and polished steel. Once the very sharp angles are softened or lost due to polishing and restoration, they are impossible to replicate, so look for unpolished examples with original proportions and textural finish.

Compare the vertical brushed grain on the case sides and between the lugs, and check for clarity of the serial and reference numbers engraved between the lugs (if not present, it’s likely a service case). A sunburst brushing effect on the case back should read ‘Tool No. 033’ in reference to the tool Heuer developed to remove the case back. Even better, this may be concealed by the original sticker.

Early dials are a darker blue, with prominent brushing and white subdials. Non-serif fonts and typeface indicate repainted or refinished dial. The original lume plots and hands will go a pumpkin colour (if yellowed/white, presume it’s been re-lumed), and the plots will often bleed into the dial paint.

Bracelet and accessories? Look for those with the original steel bracelets (made by Novavit SA) and stamped Heuer on the clasp. The fragile, original red boxes can degrade, but if present, ensure they’re correct (does the front say ‘Automatic’?). In general, though, don’t fixate on the box/papers. A good ‘naked’ Monaco is preferable to a poor example with accessories.

Ones to look for? At the top of the market is The Dark Lord, a manual-wound, PVD-coated Ref 74033N made in tiny numbers circa 1975. In 2010, the Haslinger Dark Lord sold for a huge $82,500, but it’s since settled between this and $40,000. Also, early Calibre 11 Chronomatic Ref 1133 should be found in the $25k-45k range, and more common but most iconic Ref 1133B ‘McQueen’ Monacos have settled in the $12k-18k range.

It’s lazy to call the 2016-18 price increase a ‘bubble’, but there was an inflation due to concentrated interest in the brand leading up to 2017, combined with a lack of high-quality examples available. There’s been a correction since the peak, but the market does seem robust and deeper than some expected.

The increase in prices boosted the number of examples coming to market – that these were often not great examples contributed to this correction – but outside of the steel AP/Patek/Rolex market, Heuers and specifically Monacos rightly remain long-term collector favourites.

Excerpt taken from Magneto issue 9, back issues available on our online store