WORDS: ELLIOTT HUGHES | photography: red bull, ferrari, alfa romeo racing, newspress

Although often overlooked, modern Formula 1 helmets are engineering masterpieces, blending space-age materials such as carbonfibre, Kevlar and Nomex. The latest versions used by F1 drivers are literally bulletproof, and it would be unfathomable to see a driver without one – which is why Mark Webber’s final helmetless lap of his F1 career has become such an iconic image.

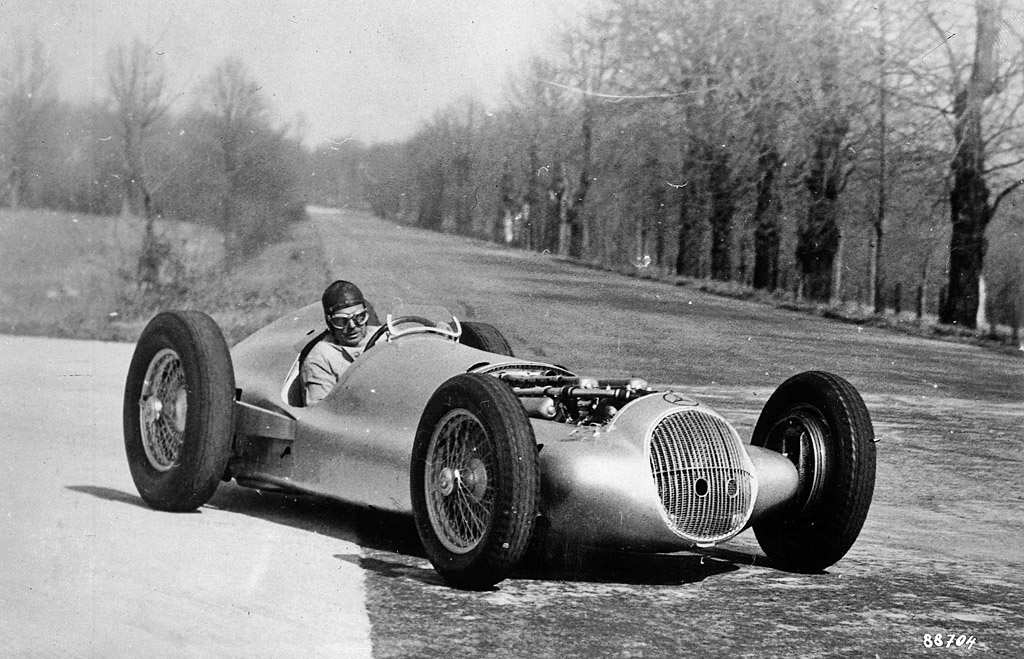

But it wasn’t always like this. In fact, the ubiquity of helmets in motor sport is a relatively recent development. The pre-World War 1 pioneers of racing made do with a simple cloth cap and goggles to keep dust from the eyes, which from a modern perspective seems outrageously dangerous. Danger was a prevalent part of life back in those greyscale times, however, and driving would have seemed like a serene activity compared with fighting in the World Wars or working in hellish mines and factories.

Predictably, it took the most perilous form of motor sport to inspire the idea of head protection: motorcycle racing. Dr Eric Gardner, a British physician, came up with the idea back in 1914 by designing a helmet with a shellacked canvas shell covering to prevent head injuries. But the idea took decades to properly catch on, and many early racers continued to wear cloth caps or leather football helmets instead.

The first somewhat protective helmets were adopted in the 1940s, and resembled little more than a soldier’s or polo player’s helmet, consisting of layers of cotton that were soaked in resin to form a hard shell with simple inner padding that sat atop the head above the ear. Although a step in the right direction, these early helmets did little to prevent devastating head injuries being inflicted in a crash.

It wasn’t until the release of the Bell 500 TX in 1954 that the first purpose-made racing helmet took shape. The 500 TX was an open-face helmet with a glassfibre-laminate construction that extended to the jawline. It was the most effective helmet of the time and was the first to be safety certified by the Snell Memorial Foundation, which was set up in 1957 following the death of William Pete Snell from a head injury in a motor race. Since then, Snell has continued to globally certify helmets for safety as well as leading research and development into helmet technologies and design.

Despite this step forward, the combination of a balaclava and open-face helmet continued to be widely used in Formula 1 until 1968, when Dan Gurney worked with Bell to produce the first full-face helmet: the Bell Star. Gurney’s motivation for a full-face helmet was more to do with the fact he was taller than other drivers and had grown tired of being struck in the face by gravel and debris rather than for outright crash protection. As well as removing the vulnerability of the face and jaw created by an open-face helmet, the Bell Star also incorporated groundbreaking fire-retardant Nomex lining, reducing the risk of serious burns in the event of a fire.

There was initially some resistance among F1 drivers in moving to full-face helmets, because many were concerned with the visor steaming up and that it wouldn’t offer enough ventilation to keep them cool during hot races. The improvement in safety clearly outweighed these drawbacks, so drivers followed Gurney’s lead in adopting full-face helmets. These became the standard by the 1970s.

With the full-face era now in full swing, drivers adopted a wide range of helmet designs from various manufacturers throughout the 1970s and ‘80s. Memorable helmets included the stormtrooper-esque Simpson Bandit of Elio de Angelis, the dual-eyeport Bell Star of Jacky Ickx and the bizarre strapless GPA model worn by Gilles Villeneuve.

The latter led to a convergence of helmet designs as the ‘80s wound on, as the twin-horseshoe clamp that kept the helmet closed failed during Gilles’ fatal crash at Zolder in 1982, leaving his head completely exposed. Niki Lauda’s crash at the Nürburgring in 1976 led to another development in driver safety. From 1979 drivers’ helmets had to be fitted with a fresh-air supply to buy them extra time if caught in a blaze. This continued throughout the ‘80s until the threat of fire from a crash was greatly reduced from advancements in car design.

Personalisation of helmet liveries was another area of helmet design that took off shortly after the introduction of full-face helmets in 1968. Simple designs such as Jackie Stewart’s famous paisley stripe and Graham Hill’s dark blue London Rowing Club livery existed prior to this, but the increase in the helmet’s size gave scope for more striking and complex designs that would become the driver’s signature. The ‘80s saw this trend pick up real momentum, as fans adored the iconic day-glo yellow helmet of Ayrton Senna, the red and white teardrop motif worn by Nelson Piquet and Nigel Mansell’s iconic Union Jack-coloured arrow design, among many others.

The 1990s saw helmets become largely what we recognise today, constructed from cutting-edge materials such as Kevlar and carbonfibre for unparalleled lightness and strength. The introduction of these materials also allowed for other features to be added to the helmet, such as fairings that prevented buffeting and aided the car’s aerodynamics. Holes for ventilation were also universally adopted in this era.

2001 ushered in another leap in helmet safety, because the FIA mandated that all F1 helmets should weigh just 1.25kg through a new regulation. This was to prevent the strain on a driver’s neck during a heavy crash, and it effectively halved the weight of helmets used throughout the 1980s.

Another big change came in 2003 when the HANS (head and neck support) device was made compulsory. The HANS device is effectively a collar that is tethered to the side of the helmet that prevents major head or neck injuries, including fatal basilar skull fractures. HANS devices are compulsory across most major motor sport sanctioning bodies today.

Innovation in helmet design was relatively incremental until 2009, when Felipe Massa suffered a freak accident at the Hungaroring when the top of his visor was hit by an errant spring that had failed and freed itself from the rear suspension of Rubens Barichello’s Brawn GP car. Massa suffered a serious injury to his skull above his left eye, and had to have a titanium plate fitted to his skull. Thankfully, he made a full recovery.

A Zylon strip was added to the top of all driver’s helmets from 2011 in response to this, reinforcing the weakest part of the helmet. Zylon is an extremely tough material that is twice as strong as Kevlar and commonly used in military-spec body armour.

The Zylon strip was removed from helmets in 2019, when the FIA brought in a new certification standard for helmets. The newest specification of helmets feature a much narrower visor aperture, and instead have Zylon woven into the shell of the helmet itself.

Thanks to decades of progress and modern technology, today’s F1 helmets are incredibly light, strong and safe. They can resist temperatures of 790°C, and resist a 225g projectile travelling at speeds of 250km/h. Visors can prevent a 1.2g air-rifle pellet from penetrating the interior and can withstand a 10kg weight being dropped from five metres, all while weighing a mere 1.4kg; a far cry from the repurposed polo helmets of yesteryear.

If you liked this, then why not subscribe to Magneto magazine today?