WORDS: WINSTON GOODFELLOW | PHOTOS: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, RM SOTHEBY’S, LAMBORGHINI AND AUTHOR

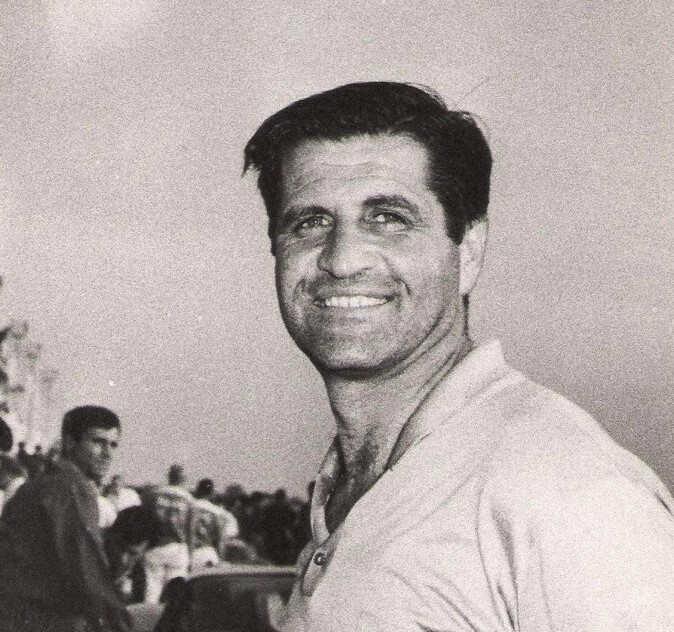

The great Italian designer and engineer Giotto Bizzarrini has passed away aged 96. Giotto was best known for creating the original Lamborghini V12, developing the Ferrari 250GTO and founding his eponymous car company. In 1981, Magneto contributor Winston Goodfellow tracked Giotto down. This is the story of his pilgrimage.

This story originally appeared in Magneto issue 13, before Giotto passed away.

Who were your sports heroes when growing up? What about guitar gods and rock stars? While I had my share on the playing field and in concert halls, the group that really grabbed this teenager in 1970s California came from Europe, most especially Italy. Typically, they were quite shapely, had four wheels and were, for the most part, the type that mothers everywhere warned you about – fast company.

That passion for Italian exotica likely germinated with a well-to-do uncle who drove a Ferrari daily. His single-headlight 330 2+2 and subsequent 308GT/4 were cool, yet the first automotive book I bought was History of Lamborghini – which, back then, was the only tome on the subject. Around that time, while perusing automotive want ads in San Francisco’s Chronicle newspaper, I saw one that said: “Ferrari looks and performance with American reliability.” The succinct description was my introduction to the Iso marque, and I bought the Corvette-powered, 140mph-plus Rivolta 2+2 for less than the cost of my brother’s Ford Pinto.

Iso and its models quickly captivated me, if for no other reason than decades before you could say “hey Siri” for answers, you had to become a serious automotive detective to discover anything. Very few people knew about Isos back then, and the more I investigated the marque the more it fuelled my wonderment of Italy’s exotic car scene and history.

Especially because one name kept popping up – an engineer named Giotto Bizzarrini. Who was this guy, and what was his back-story? How did he end up working for Ferrari, Lamborghini, Iso and more? He even made cars under his own name, and was that ever a maze to sort out. Then there was the most perplexing question of all: If Bizzarrini was indeed an exotic car sports/rock star everything portrayed him to be, how come he completely disappeared? In fact, was the dude even still alive?

Unknowingly, the first piece to solving the Bizzarrini puzzle was forming the Iso & Bizzarrini Owner’s Club with fellow enthusiast and Iso owner Louis Vandenberg. An individual who joined the IBOC early on was Earl Waggoner; he visited Iso in 1966 and knew an ex-pat Italian who consulted for the company in 1964-65. Rino Argento was a friendly Piero Taruffi lookalike who offered first-hand insights into Iso and Bizzarrini but had lost track of the mercurial engineer.

He had an idea, however. A good friend was Franco Lini, a former Ferrari team manager who was one of Italy’s top automotive journalists. “If anyone knows where Bizzarrini is,” Rino said, “it’s Franco.”

A meeting was arranged, and in October 1981 I travelled to Las Vegas for the inaugural Caesars Palace Grand Prix. Franco was covering the race, we hit it off, and he offered to help in my quest. Several weeks later I boarded a plane to Europe and Italy for the first time, and while there Franco delivered – big time. I can still hear his Alfa GTV Turbodelta’s engine coming on boost as we sailed past cars while heading to Livorno, the location of Bizzarrini’s old factory. Franco was an enthusiastic living encyclopaedia of Italian automotive history, so on the trip I peppered him with questions on Iso, Bizzarrini and other obscure marques and people.

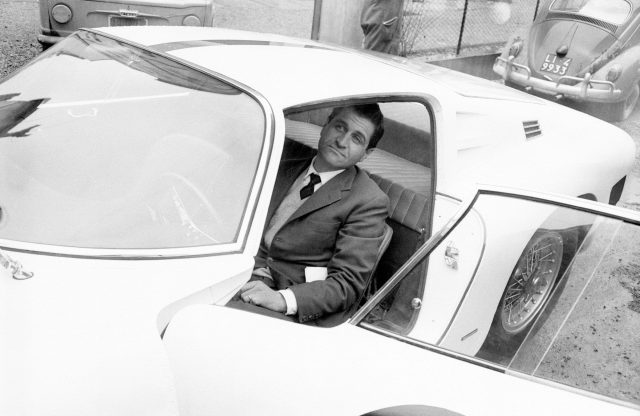

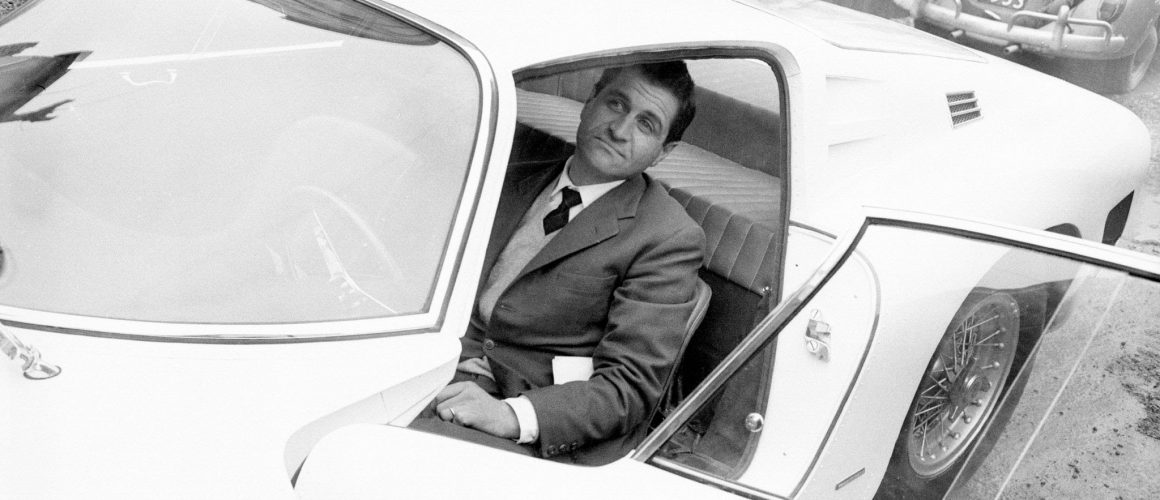

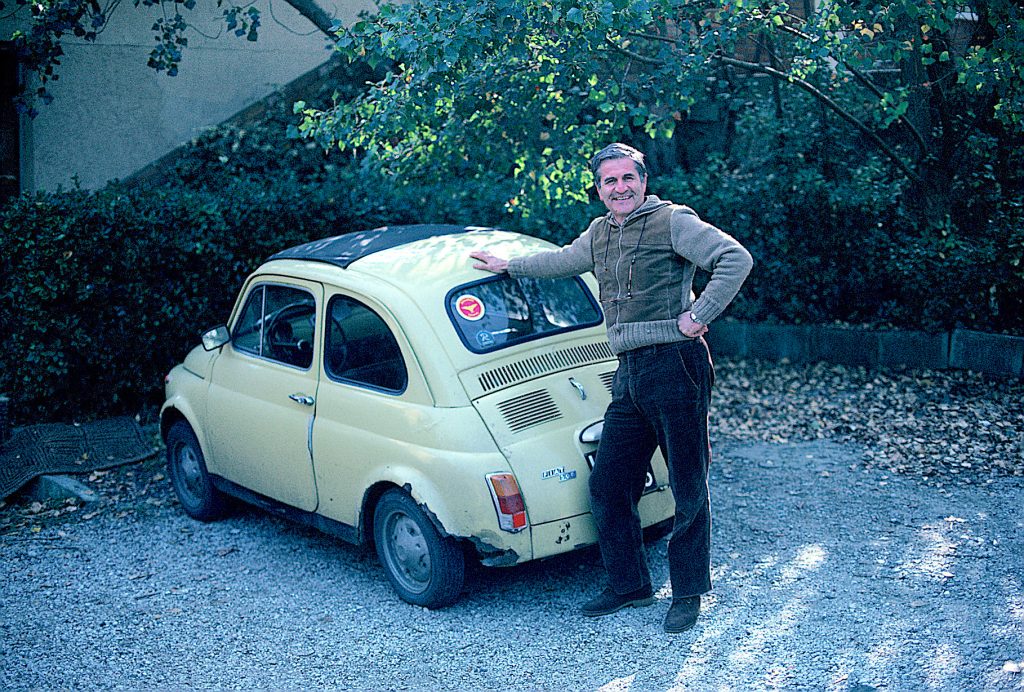

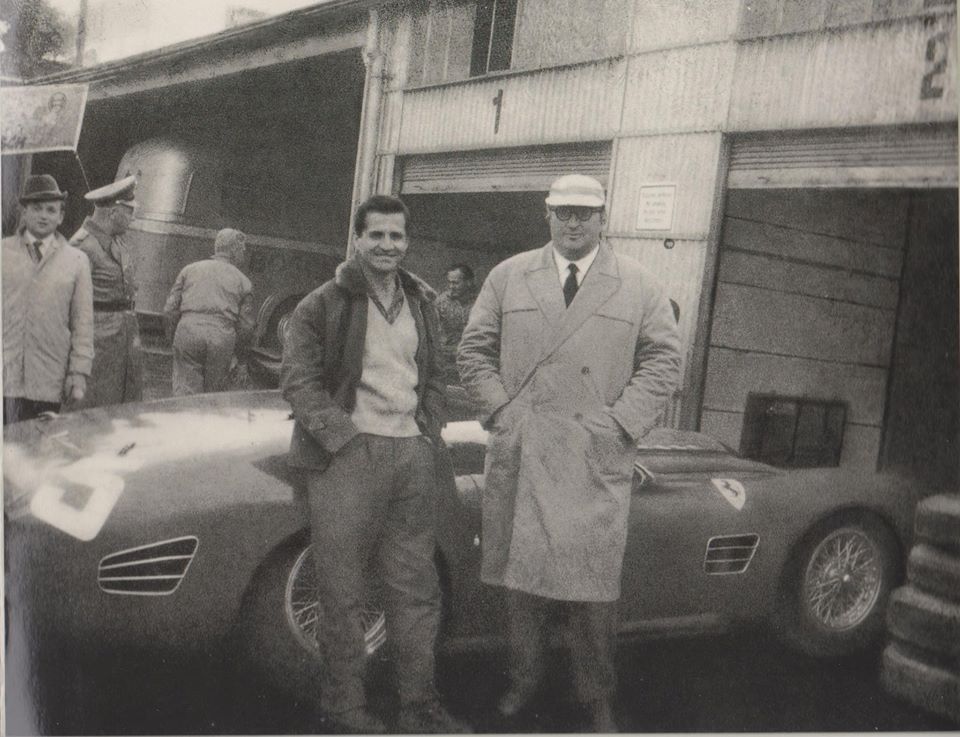

We stayed in a hotel near the coast, and the following morning drove to a rendezvous point in the hills outside Livorno. Franco found a pay phone and placed a call. Several minutes later up came a somewhat tatty Fiat 500, and out jumped the elusive engineer. Casually dressed, Bizzarrini was a short, stocky man with a full head of hair, a handsome, weathered face and a soft smile that belied the hardship I would find out he had endured. He and Franco greeted each other like the long-lost friends they were, and after introductions, we followed Bizzarrini to his house. A sinewy road barely two lanes wide wound its way through the rolling hills, Franco and I chuckling because his 150bhp Alfa was frequently on boost to keep up with the smoothly (and expertly) driven 20bhp-odd Fiat.

We eventually turned off the rustic strada, went down an unpaved driveway and parked near Bizzarrini’s modest but comfortable country home. Scattered around the property in overgrown brush were partially completed bodies, jigs and forlorn frames, all relics of his car-building and engineering days.

Giotto’s wife Rosanna warmly greeted us at the door, and I must have been grinning ear to ear. Not only would I be spending time with my automotive ‘sports hero’, but by then I had pieced together enough on the man, his career and more to ask some reasonably intelligent questions. Franco would act as translator and history guide, and after the two caught up on life I turned on the tape recorder and we started our conversation – the first of many we’d have over the ensuing decades. Later a meal was offered, and Mrs B proved to be a fantastic cook; her tortellini alla panna became my favoured dish on subsequent visits.

We began by examining Bizzarrini’s early career and how, at age 31 in 1957, he joined Ferrari. “It was simple,” he said, unknowingly illustrating the tightly knit nature of Modena’s grapevine that existed back then. Several months after Giotto graduated with a mechanical engineering degree from the University of Pisa in 1953, he was hired by Alfa Romeo’s experimental department, where he quietly but steadily built a name for himself. A cousin in Florence worked with the brother of prominent Ferrari engineer Andrea Fraschetti, so he knew of Bizzarrini.

“One of Ferrari’s test drivers died,” Giotto recounted, “so Ferrari asked Fraschetti to find another, hopefully one who was also an engineer. The Fraschettis talked and the brother suggested me. Of course, I rushed to Ferrari.” Not long after that hiring, Fraschetti tragically perished while testing, and Giotto suggested Carlo Chiti, a cohort at Alfa, who would go on to become Ferrari’s chief engineer.

Bizzarrini and his uncanny feel for a car saw him work as “a test engineer/test driver”. He eventually became “controller of checking on experimental, sports and GT cars”, and in this role he cemented his reputation. Many of the era’s greatest Ferraris were engineered and tested by him – the pontoon-fender 250 Testa Rossa, SWB, Cal Spyder and the most famous 250 of all, the GTO.

When queried about the atmosphere at Ferrari, Giotto replied: “I never heard about financial difficulty. I never heard Ferrari say: ‘We spend too much money, we have to be careful.’ This was very important for an engineer, because we had freedom.”

I then asked if the GTO was an evolution of prior models or was Ferrari trying to beat someone in particular. “It was Jaguar,” Bizzarrini replied. “Because Jaguar made the E-type, which was presented at the 1961 Geneva Motor Show, commercial manager Girolamo Gardini said: ‘It will be a disaster! They are going to beat us with their competition GT.’ Ferrari said to me: ‘We have to do something.’ In response, we built a completely new car, the first one made entirely in the experimental department – even the body. We got a young boy and he built it. It was so ugly that we used to call it ‘the Monster’.”

Shortly after testing on the GTO prototype commenced, Giotto became embroiled in the ‘Palace Revolt’, a murky episode involving Ferrari’s highly respected, influential sales manager (and E-type protagonist) Gardini. Asked why it happened, Bizzarrini replied: “Nobody knows the real truth, because there are so many reasons. Ferrari fired Gardini, and as soon as this was found out a group of us tried to unify to support Gardini, and have Ferrari bring him back. Ferrari said ‘no’, and fired everybody.”

The renegades were Bizzarrini, Chiti, Gardini and several others, with the firing initiating Giotto’s time as Italy’s top engineering gun for hire. His first stop was ATS (Automobili Turismo e Sport), primarily put together by Chiti and Gardini to combat Ferrari on the track and street. They rounded up serious financial backing from prominent Ferrari client and top privateer Count Giovanni Volpi, industrialist Giorgio Billi and tin-mining heir Jaime Ortiz-Patiño. The Formula 1 effort would be a disaster, the luscious 2500GT the first mid-engine supercar.

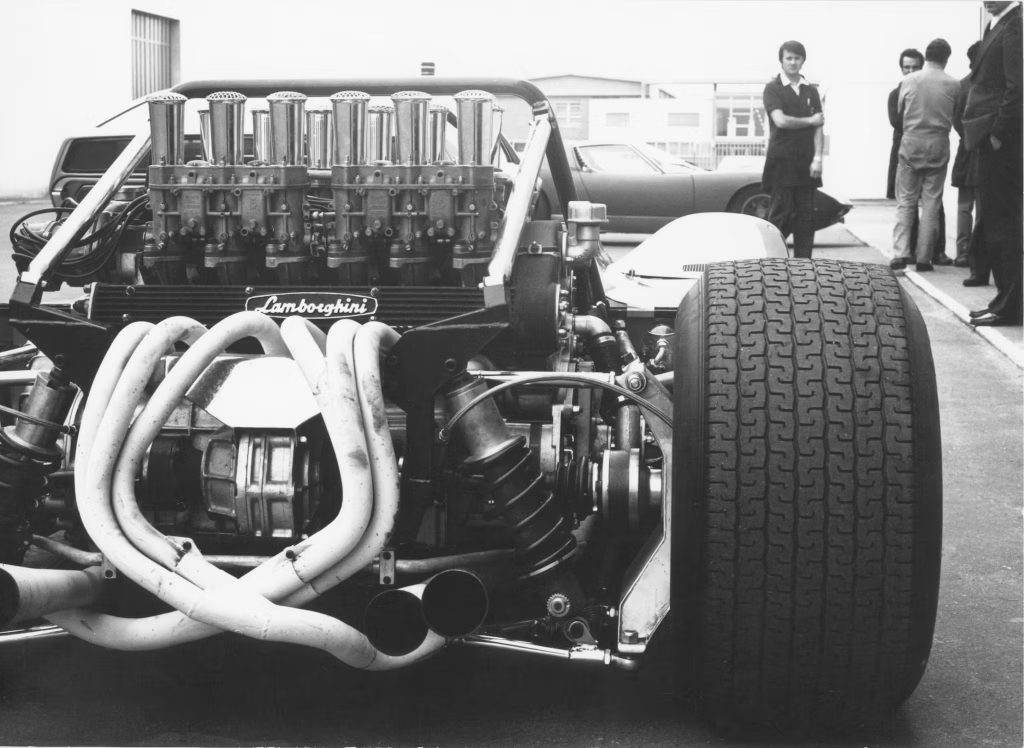

Giotto was long gone before either debuted, but I discovered an intriguing ATS-inspired nugget during a 1993 conversation. Ferruccio Lamborghini commissioned Bizzarrini to design a V12, and for decades it was written that the engine was created while he was at Ferrari. “Absolutely not,” Giotto said. “When I left Ferrari, I was never thinking of an engine.”

Instead, ATS was a blank canvas, so there was a debate on what type of motor its cars should use. “Gardini always started with an F1 engine,” Bizzarrini pointed out. “That’s why my design was 12 cylinders, 1.5 litres. First F1, then would come a production car. It was, in essence, to show Gardini what I could do.”

When ATS went with a V8, that and shareholder troubles prompted Bizzarrini to leave the company. Giotto was thus prepared “when Lamborghini came to me, thanks to Giorgio Neri and Luciano Bonacini. At Ferrari they were considered the best in Modena. Count Volpi always worked with them. They had a dyno room for testing, and were able to construct a new engine. But they were not designers, engineers; rather, people would come to them to have them build it.”

At the time Bizzarrini knew “nothing at all” about the aspiring car constructor, but his relationship with Neri and Bonacini gave him confidence to present the ATS-inspired V12 drawings. When they met, Lamborghini said: “I am not thinking about F1 or racing. I want a car like Ferrari, for the highways. Twelve cylinders is okay, but it needs to be 3.5 litres…”

The two wrote a contract stating that the engine had to produce “…350bhp. For every ten horsepower less, there was a reduction in the percentage of the balance to be received”. Bizzarrini took a down payment and went to work. The V12 ended up exceeding the benchmark, but needed refining to run properly at low rpm – and this led to a vociferous disagreement. “I was expecting Lamborghini to say: ‘Bravo! Thank you,’” the engineer recalled. “Instead, he was very aggressive. This caused me to have a bad reaction; I thought we were going to have a fight.”

Bizzarrini did get paid, but he recommended engineer Giampaolo Dallara (ex-Ferrari, then at Maserati) to complete the V12 and more on the 350GTV, Lamborghini’s first car. The finished engine and the subsequent enlarged variants powered Lamborghinis for several decades.

Another client in 1962-63 was ex-ATS shareholder and Scuderia Serenissima patron, Giovanni Volpi. In a February 1994 interview, the Count told me: “I was supposed to take delivery of the first two GTOs, then the ATS thing happened. I got a call from Ferrari, telling me to forget it, so I made one in two weeks.” Volpi’s ‘GTO’ was the Breadvan.

A heavily modified 250SWB masterminded by Bizzarrini, the Breadvan’s memorable moniker came from the French press, who saw it at Le Mans and were startled by its avant-garde coachwork. “Bizzarrini moved the engine back 12cm, so it was like a front- mid-engine design,” Volpi remembered. “The car was very light, and while the bodywork was rudimentary, it was like the J-car Ford GT40 with a chopped back.” Volpi said the Breadvan ran away from the GTOs at Le Mans but was a DNF. Later in 1962 it proved its mettle with three top-five finishes and two class victories.

Giotto also designed ASA’s 1000GTC endurance racer, which resembled a miniature 250GTO, and did development testing on the road-going 1000GT. The diminutive four- cylinder production model started life as the ‘Ferrarina’ inside Maranello and, as Bizzarrini recalled in our November 2001 interview: “Enzo suggested the contact with ASA.” While the 1000GT was well received, its high sticker price saw fewer than 60 made over five years.

A much more ambitious effort, one that greatly influenced Giotto’s career through the remainder of the 1960s, came from Milan industrialist Renzo Rivolta. In the 1950s his Iso company was a very prosperous manufacturer of motor scooters, motorcycles and small industrial vehicles. Iso also created and made the innovative Isetta city car, licensing its production to BMW and others. Renzo loved speed, and after being disappointed by the finicky nature of the GT models he owned, Iso entered the burgeoning gran turismo space in 1962. Rivolta hired Giotto not only for his test- driving and engineering acumen, but to bring credibility to Iso’s effort by constantly promoting Bizzarrini’s name and Ferrari credentials.

Working with Iso was the first time Bizzarrini sampled a Corvette engine. In one of our 1992 talks I asked what he thought of it. “No one in Italy knew about that engine,” he said. “I felt it was superior to Ferrari’s, and was very surprised by this. It had immediate throttle response, with power that was similar to the Ferrari’s.”

Iso’s first model, the Rivolta 2+2, entered production in 1963, but where Giotto truly made his mark with Iso was the legendary Grifo. Two versions broke cover at 1963’s Turin Auto Show – the A3/L (a street-going GT), and the competition-oriented A3/C. Giotto fathered the latter, feeling Iso needed “to have an exciting flag, like a sporting activity – to be in racing”.

By now his small Autostar facility in Livorno was up and running, and with competition in his blood, he pushed racing’s benefits. An agreement was made where he would build Iso’s racers, and the road-going A3 Stradale offshoot.

The A3/C reflected Giotto’s thinking, as everything was done to optimise performance. A front-mid-engine design, the 327ci was placed so far behind the forward axle that the distributor was accessed by removing a panel on top of the dashboard. Anything that could be removed to lighten things up was, the resulting kerbweight listed at just over 2500lb. He also devised a cross-draught Weber set-up that bumped horsepower to over 400.

Reflecting on the A3/C in our 1981 conversation, Bizzarrini said: “It had the possibility to be GT class World Champion for three or four years,” to which Franco Lini agreed. In a later interview Giotto noted a strong interest in the Iso-developed A3/L, because its chassis was basically identical to that of the A3/C. If the right number were produced, he said, the A3/C would compete in the GT class. “For homologation,” he noted, “100 cars was the number, but the real figure was lower. Ferrari did only around 30 GTOs.”

Unfortunately, Rivolta couldn’t fully support racing, nor an immediate ramp-up of A3/L production because the latter needed refining, and Iso’s cash flow took a nosedive when the US importer reneged on its contract. Still, the A3/C was an effective track weapon; one would place 14th overall and first in class at Le Mans in 1964, another – further modified and entered by Giotto – ninth overall and first in class in ’65.

The A3/L eventually became the 160mph Grifo GL, customers lining up to order what Autocar described as “the ultimate in transport”. But by then it was too late, because Iso and Bizzarrini had parted company. Twenty-two Grifo A3/Cs and Stradales were built in 1964-65. Bizzarrini moved to a larger facility in Livorno, and continued production under his own name. The Isos became the Strada 5300 and GT America – the latter having a glassfibre (instead of aluminium) body and an independent rear suspension (in place of the de Dion). Italy’s Quattroruote test Strada hit 100mph in 13.7 seconds, and saw 161mph. As quick and fast as the car was (the testers felt it would clear 170mph with taller gearing), what most impressed them was “the road holding”. Road & Track’s December 1966 cover test of a GT America concurred, noting its “handling borders on the fantastic”.

Giotto also made several Bizzarrini Corsas, including one that competed at Le Mans in 1966 under the marque banner; it later became the GT7000 when fitted with a Corvette L88 (a 550bhp 427ci), and had a listed 340kph (210mph) top speed. Another big-block car was the Nembo, done by Neri and Bonacini. Built for Holman- Moody in the US, there was one issue, Giotto said in 1982: “Ford didn’t supply the engine.”

As the brand established itself with a small but consistent stream of Strada and GT America orders, in late 1965 an opportunity with real sales potential landed in Bizzarrini’s lap. “A man who had made a lot of money building on speculation in Rome approached me at the Turin Auto Show,” Giotto recalled. At the time the Government was promoting industrial development in southern Italy. “The man said: ‘Why not do a 2.0-litre GT for the middle class?’ The plan was to ask the Government for funding and build the plant.”

Enthused by the idea, Bizzarrini designed and developed the GT Europa out of his own pocket. The prototype featured a Fiat 1500cc engine and five-speed transmission, and when completed he met the potential backer. “When I was talking with him,” Giotto said, “I realised the Government money was to go in every direction except building the car.” The engineer promptly walked away.

Still, with the new model in hand, he presented it at 1966’s Turin Auto Show, where it garnered much attention. “Entirely new and very interesting was the Europa 1900,” Road & Track’s show coverage noted. “This car is styled along the lines of the big-banger Bizzarrini, but is smaller and powered by an 1897cc inline four-cylinder Opel engine.” Giotto said the engine change came from his connection with GM, and production was slated to start in 1967.

The Europa wasn’t Bizzarrini’s only debut in 1966. A personal favourite is the Spyder SI that was introduced at Geneva, and when I discovered Pete Coltrin’s brief report and photos in Road & Track’s August 1966 issue, my automotive lust shifted into overdrive. Giotto slightly burst that bubble when he said that car was a non-runner, but he then noted two actual cars were produced. These open-air Bizzarrinis used Strada or GT America underpinnings and reliable Corvette drivetrains, and in 1982-83 I found the last one made. I purchased it for Californian Iso owners Howard and Jane Turnley, put several hundred miles on it in northern Italy (including at Monza), and later did the same in California.

As the number of Bizzarrini models grew in 1966, ironically what he loved most – competition – proved to be the start of his undoing. He still sold the Corsa, but he knew his front-engine racer was becoming obsolete. During his time with Iso he proposed a true mid-engine car, the concept leading to some Giugiaro renderings in 1964. Now that he was on his own, he literally bet the farm on designing and developing his own mid-engine racer.

Giotto started working on the P538 in 1965, and it had a tubular frame, swoopy aerodynamic open coachwork and a longitudinally mounted engine. While the name referenced the model’s 5.3-litre Corvette V8, American racer Mike Gammino (who drove an Iso Grifo A3/C at Sebring in 1965) “contacted me in 1966 and said he wanted a Bizzarrini chassis with a Bizzarrini engine. That’s why I did a P538 with a Lamborghini V12”.

That was chassis 002. Chassis 001 was presented in February 1966, but it slid off a wet track during demonstration testing and was damaged. Not having massive cash reserves, Giotto raided it for parts to use on Gammino’s car, then built chassis 003 to race at Le Mans where it would be a DNF. [Ironically, I came across the cannibalised (and thought lost) P538 in Switzerland in 1982.]

“The P538 was a big financial disaster for me,” Giotto said – noting that he sold everything he owned to create the car, figuring it would compete for three or four years. But a shock came in 1967 when the CSI: “Changed the rules. They made prototypes 3.0 litres, and sports cars 5.0 litres with 50 cars having to be built. The problem was building 50 cars.”

Franco Lini grasped the impact the sudden change had on his friend. He was then managing the Ferrari team, and recalled telling Le Mans they wouldn’t see any Ferraris in 1968 because: “Ferrari doesn’t have the money to build 50 cars – which meant it was a complete disaster to Bizzarrini because he was not Ferrari. He was a single man, with all his fortune invested.” Giotto soldiered on, attempting to lessen the blow by enclosing the Le Mans racer and trying to sell it as a road car. This led to the Duke of Aosta, a favoured client, commissioning a one-off. The aptly named Duca d’Aosta was built in 1968, and had a 365bhp 327ci, a five- speed transaxle and a claimed top speed of 320kph (200mph). It was slated to appear at Turin in 1968, but wasn’t completed in time.

Still, the Bizzarrini nameplate headlined the show. Because the enclosed P538 didn’t sell, Giotto listened when Giorgetto Giugiaro called him. The ambitious ex-Bertone and Ghia chief stylist had formed his own firm, Ital Design, and suggested: “You build the chassis and I put the body on it, and then we sell the car and spilt the profits.” The Le Mans P538 became the donor chassis, Giugiaro went to work, and the wedgy Bizzarrini Manta with three-abreast seating and central steering was Turin’s star attraction.

Surprisingly, neither Bizzarrini nor Giugiaro made a penny on the car, for during a trip to the US it was lost. When it eventually returned to Italy, it sat in customs unclaimed for years. It was bought by a collector in Cuneo, which was where I found it on that first European trip.

Bizzarrini also attempted to keep his company afloat via outside funding. A lawyer friend introduced him to three investors, whose capital infusion brought temporary reprieve. They requested a 2+2 to broaden the product line, which Bizzarrini built. But as Giotto related, two of the three weren’t what they appeared to be (one excelled in “dirty affairs”), and they used bank leverage and a sophisticated shell game to bleed the company while Giotto minded the store.

This went on until August 1968, when Bizzarrini learned that some creditors hadn’t been paid. Assets were seized and credit lines closed even though the company was operating “at break-even or slightly in the black”. The unseen financial shenanigans caused Giotto’s world to rapidly unravel, just as his company was on the threshold of a new model boom (Duca d’Aosta, Spyder SI, 2+2) and one of the year’s wildest show cars, the Manta.

The firm liquidated in mid-1969, but Bizzarrini seemed to get a reprieve when Giugiaro and others recommended him to the American Motors Corporation. “There was a meeting with an acquaintance who represented AMC to see if I would do work on a car styled by Dick Teague,” Giotto remembered. “They wanted to know if I could do a chassis and more for a mid-engine car.”

Bizzarrini bit, and he ended up designing the AMX/3, working with BMW during development testing. In March 1970 the mid- engine AMC was presented to the press in Rome. “Cautious optimism seems to describe American Motors’ plans,” Road & Track reported, and Bizzarrini felt the same. AMC gave the green light, he further developed the car, and a small production line was set up in Turin.

Unfortunately, right as production started, AMC got cold feet – possibly because of the recently debuted De Tomaso Pantera. AMC encouraged Bizzarrini to make 30 cars under his name, stating that it would purchase ten. But Giotto was tormented by the recent bankruptcy. “It was so fresh on my mind,” he lamented. “I didn’t have the courage to do it.”

In ’71 at Turin, he displayed an AMX/3 called the Bizzarrini Sciabola, alongside a heavily modified Europa with a mid-mounted Fiat 128 drivetrain. The following year he consulted for former employer Iso on its mid-engine Varedo and more, and in 1973 he entered an intriguing ground-effects barchetta in the Targa Florio. It was quick but retired on the first lap.

Then Giotto pulled his disappearing act and left the auto industry, becoming a professor at his alma mater, the University of Pisa. He consulted for Yamaha and Kawasaki, and built the occasional private commission, such as two Lamborghini-powered P538s for a Turin-based collector.

After our paths crossed in 1981, I visited him as often as possible. In 1990 the Bizzarrinis and several friends came to California, staying at the parents’ house before we headed to Monterey for the IBOC’s annual meet and the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, where Giotto was the headline feature.

By then the modern supercar boom was underway, and Bizzarrini’s name was again making headlines. There was a potential F1 effort out of America that remained stillborn. Then came the mid-engine Picchio project that targeted becoming “the Lotus of Italy”; only one was made, thanks to the severe recession of the early 1990s. After the Picchio was the Ferrari Testarossa-based BZ2001, which also remained a one-off for the same reasons.

Still, all this reinvigorated Giotto’s spirit, which led to much experimentation. Later projects included the Kjara (a lightweight barchetta featuring a Lancia diesel engine and electric motors), the BEBI (another lightweight barchetta powered by a Kawasaki engine) and more. As new ideas germinated – some a bit out there and unrefined, others very intriguing – he continued to push boundaries on himself, machinery and the people around him.

Over the years I saw many sides of the man, from endearing host to despondency while discussing the difficult periods. I witnessed joy in reliving his accomplishments, and volatility where he could explode at the drop of a hat – a trait that didn’t exactly endear him to some of those he worked for, and with. And his coming back to life. “I feel like I’m 28 again,” he gleefully proclaimed in 2003 as we caught up at Lamborghini’s 40th anniversary bash.

Recently his health has been on the wane, and no one knows how much longer he will be with us. But that hasn’t diminished whatever the mystique is that surrounds his name – witness Pegasus Group’s concerted effort to resuscitate the marque. Which isn’t too bad for a sports hero who all but vanished nearly 50 years ago…