WORDS: ALEX GOY | PHOTOS: BENTLEY

A flash of something a little out of the ordinary can kickstart the most incredible things. In Brian Gush’s case, it meant a journey to the top step at Le Mans, some rather unexpected battles and a meeting with an actual king.

Gush was working for Volkswagen before, post Group acquisition, joining Bentley as director of chassis and powertrain. His job was to make sure existing product got the send-off it deserved, and to work on the car that would reinvigorate the company, the Continental GT.

At the time, Bentley had a bit of an image issue. Your grandad bought a Bentley, your slightly sweaty uncle had a Bentley, Alan B’Stard had a Bentley. Despite an incredible history, a fusty stench followed it. For the new Bentley that simply wouldn’t do – and thanks to Gush hearing about a cancelled VW Le Mans programme, it found some fast Febreze. The best way to make Bentley cool would be to go racing at Le Mans, where the legendary Bentley Boys went to play. And to win.

Bentley being Bentley, it didn’t do things quite the same way as everyone else

“I came across a VW compatriot who had started a Le Mans programme, which had then faltered because the engine hadn’t produced the goods. They had the genesis of a car, they had a car on the drawing board, but no engine for it. So I got chatting to him about it…”

The spark of an idea was there, but at the time the VW Group’s top tier Le Mans efforts were directed firmly at Audi. This would be both a positive and a negative for the Bentley – having two VW-backed teams tackling Le Mans could cause a little upset, but it did mean there was a proven engine not far out of reach. Well, within reason…

“I knew Dr [Franz-Josef] Paefgen, who was head of Audi at the time, because he was on our supervisory board at VW. I went along to him on a Sunday morning and said: ‘If I could put a Le Mans programme together, would you sell me an Audi customer engine?’ He replied: ‘If you can get that past your PR guys… a German engine in a British car?’ I said: ‘If I can get it past, will you shake on a deal?’ He’s loving it, and said ‘yeah’. He shook on the deal.”

Engine secured, work began on the car. You’d think that a competition Bentley with an Audi engine would cause some issues, but Gush had a plan to make all those worries go away. The package was all new: a fresh monocoque made in the UK; a Bentley livery; engine attached to a British Xtrac gearbox, and all the trimmings.

“In that first car, and in all the cars over the three years, there was more British content in the Bentleys than there was German content in the Audis. The Bentley’s wheels came from Italy and the engine came from Germany, but that’s it. The Audi’s tub was made at Dallara in Italy, the wheels came from Italy, the gearbox came from the UK.”

The car wasn’t, Gush notes, a carry-over of a cancelled Audi: “The interesting thing is that RTN, a company in Norfolk, UK had been building the Audi R8C, but that project had been scrapped. There was nothing left of it. There was no component common between that car and the Bentley, not one thing… I mention that because a lot of people thought the Bentley was a continuation of the Audi R8C.” It’s a cause of great frustration, clearly: “Anybody who says it disqualifies himself as an enthusiast. It touches a button.”

Still, with a car put together Gush was onto the next step. The project needed cash, and plenty of it. To get that you need to convince people with it to hand it over – and persuade them that your reasons for needing it aren’t simply ‘fun’. To do this, Gush needed to go to the VW board and make his case. The man at the top was rather familiar with Le Mans; Ferdinand Piëch had masterminded cars that had done rather well there after all. No pressure then.

“That was a career-defining meeting. He wasn’t entirely prepared for it. He knew we were going to show him something. I had the car there, very few people in the room, and said: ‘Right, can we go?’ He said: ‘I’ll think about it.’ He had quite a lot of questions, but then I’m presenting to the father of the Porsche 917.”

From here Gush was invited to put a budget together, which posed its own problems. The VW Group had a whole host of cars competing, each with their own rather substantial coffers. What do you do when you’re not only starting from scratch, but are also going up against budgets like that? There’s a risk you’ll pitch too high and be told where to go pretty swiftly. The Bentley budget started at a ‘zero base’ – essentially what everything would cost starting from scratch.

The team owned nothing, employed no one and had nary a bean to its name. Math was done – world-class math at that – and Gush was told his budget was wildly wrong… but not for the reasons he’d thought. “We were substantially less expensive. Zero-based budgeting means you don’t have a precedent, you just go in with ‘what do I need to do to be competitive?’ There was no fat in it. What I didn’t know was where the others were in their budgets. All of a sudden I was under-pitching them by a substantial margin.”

Gush was told that he needed to up his demands substantially, because top brass was sure the project would run dry and he’d come back begging. So he did – but, he adds with a grin, he stuck to his original numbers and gave the excess back.

From there the Bentley team was away. There was a three-year plan: turn up and see what happens in year one; podium in year two; win the whole thing in year three. Easy!

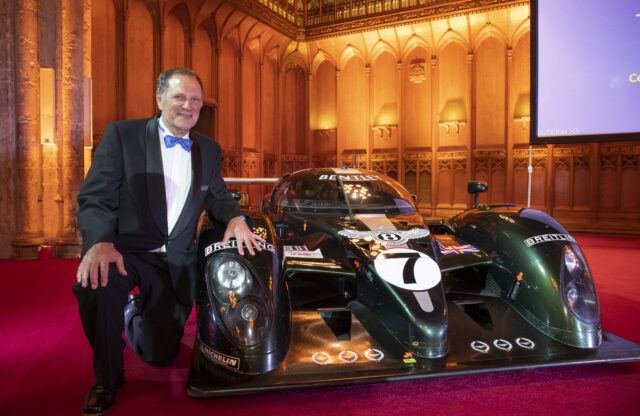

The first car wasn’t quite what the team had hoped for. It was very much on the ‘prototype’ end of prototype racing – lumpy at low speed, occasionally recalcitrant and not proven in every condition. At the 2001 race, heavy rain got into the gearbox actuator of the No. 7 car driven by Guy Smith, Martin Brundle and Stéphane Ortelli, and took it out of the race. The same had happened to the No. 8 car driven by Andy Wallace, Butch Leitzinger and Eric van de Poele, but a repair kept it running all the way to a third-place finish. Considering the team wasn’t supposed to get that far so quickly and the car wasn’t ideal, the Bentley return was going well.

A win, reckoned Gush, was within reach, but not with the 2001 car. He went to then CEO Dr Paefgen and told him the team would need a new car. It was feasible, but to make the numbers work the Bentley team could only run one machine in 2002 on half the budget – pushing the remainder over to the new racer.

While the idea of splitting the budget down the middle seemed sound, it doesn’t quite work like that. Half the cars don’t equal half the cost, it means one car is more expensive. Still, one ran at Le Mans 2002 and managed fourth place. Not bad for a car that the team wasn’t planning on developing.

Work began on a new, purpose-built Bentley. This one, with the benefit of a little extra cash backing, wasn’t going to be anything but utterly perfect. “The new car did everything that we originally wanted to do but couldn’t.”

As well as the right car, the right people were going to be involved as well: “We cherry-picked the people we wanted. They were really good. We got really good guys. Tom Kristensen, Dindo Capello, Guy Smith – who I’d kept on as a reserve driver in 2002 when I had to reduce to one car – and then David Brabham, Johnny Herbert and Mark Blundell. We had a formidable line-up.”

A brand-revitalising race programme, a new car and all the people management that goes with it is enough to keep anyone busy. While all that was going on, Gush was revising Bentley’s road range, and overseeing the development of the Continental GT. Two quite large jobs, but he managed them with glee: “I was young and ignorant and full of energy. At that age, you tackle it. It was an adrenaline rush. It was fantastic. I was doing road-car development by day and race-car development by night. It was great.”

Bentley being Bentley, it didn’t do things quite the same way as everyone else. It put itself on display at Le Mans. It opened its doors to all, let them take all the pictures they wanted, and didn’t care who saw what. “How can you [other teams] copy the engine on the day of Le Mans? Why would you ask a journalist to put his camera away on the day of the race? What are you going to re-engineer?” They gave the world, as Gush puts it, a seat in the kitchen.

Opening the doors meant plenty of people wanted a look in, including, in 2001, King Carlos of Spain. “He came in, and I asked what I could show him. He said he’d love to see a pitstop, so I told him to come with me. We stood on the garage wall under the petrol bowsers and he watched the pitstop. He came to me afterwards and said: ‘That was amazing.’ His bodyguards were going crazy in the back of the garage.”

Bentley’s approach was a sound one. Its catering had linen napkins, proper salt and pepper grinders, and the fineries the Bentley Boys of old would expect. “We took a different approach to it; we were building a brand doing something we loved.” And they got involved with the fans as well: “After the 2001 race, some Bentley Boys set up a table on the track with a white tablecloth, serving Champagne, and they invited us to join them. We went and sat at the table. It was great. It’s a little bit eccentric, but it’s part of the whole thing. We’re going racing. We’re not compromising at all.”

The 2003 Speed 8 was a vast improvement over the old car. Qualifying first and second, the race went almost flawlessly for both runners, and both came over the line in not only first and second respectively, but also in the same shape in which they’d started 24 hours earlier. Gush’s three-year plan had come to fruition. Year three: win Le Mans.

What next? “After we won the race, we were in a position to win it in 2004, clearly.” He returned to Bentley with a lower budget and hope in his heart, but was asked what he would do differently in 2004. “The same again,” was his answer. “That’s not an improvement,” he was told. And with that, Bentley’s return was done. What more could the cars do? You can’t get a double first place.

Would Gush change anything? “I wouldn’t do anything differently. There are some areas where you look back and note where we could have done better, but you couldn’t improve on the result.”

The legacy the Speed 8 left behind is incredible. It brought Bentley the team’s first outright Le Mans win in more than 70 years, it showed a new generation of race fans that Bentley wasn’t just for their grandads any more, and it gave a little bit of that ‘win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ magic to the, then yet-to-be-launched, Continental GT. What would have happened if Gush hadn’t seen that VW? The GT would still be well known, sure, but the world would have missed out on one of the best-looking cars ever to win at La Sarthe.