The National Motor Museum’s quest to restore Sir Henry Segrave’s 1927 Sunbeam 1000hp Land Speed Record holder and return it to the sands of Daytona Beach 100 years after it first broke the 200mph barrier is an epic undertaking. At the Beaulieu Autojumble, one of its two engines was fired up for the first time in 90 years.

We’ve been following the rebuild for a few years now, and ran the following story by John Mayhead in Magneto issue 21.

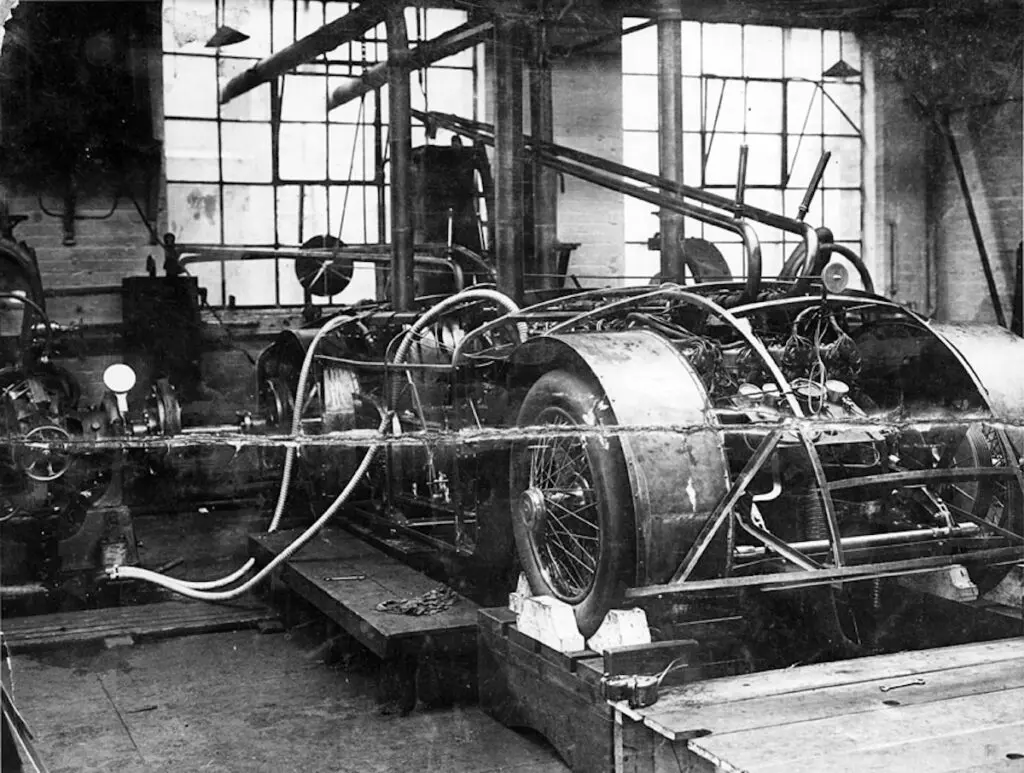

“The engines were started up and the whole building shook. No words can describe the unimaginable output of power which the 1000hp machinery seemed to catapult into the building. It was one continuous deafening roar. The very walls quivered, while the tiles on the roof seemed to dance… I think I stood and stared at the monster as a child would have done. It is the only time I can honestly say when I have stood in front of a car and doubted human ability to control it.”

Henry Segrave’s description of hearing the twin Matabele aero engines fully fire up for the first time, in a cradle at Sunbeam’s Moorfield works in Wolverhampton in early 1927, wasn’t an overreaction. Nobody had tried to push the Land Speed Record over 200mph – let alone with a four-tonne, 23ft 6in car powered by engines displacing nearly 45 litres. Everything, from the coupling shaft to the special honeycomb radiators, had to be designed for an environment that existed only in an engineer’s notebook. Some said it couldn’t be done.

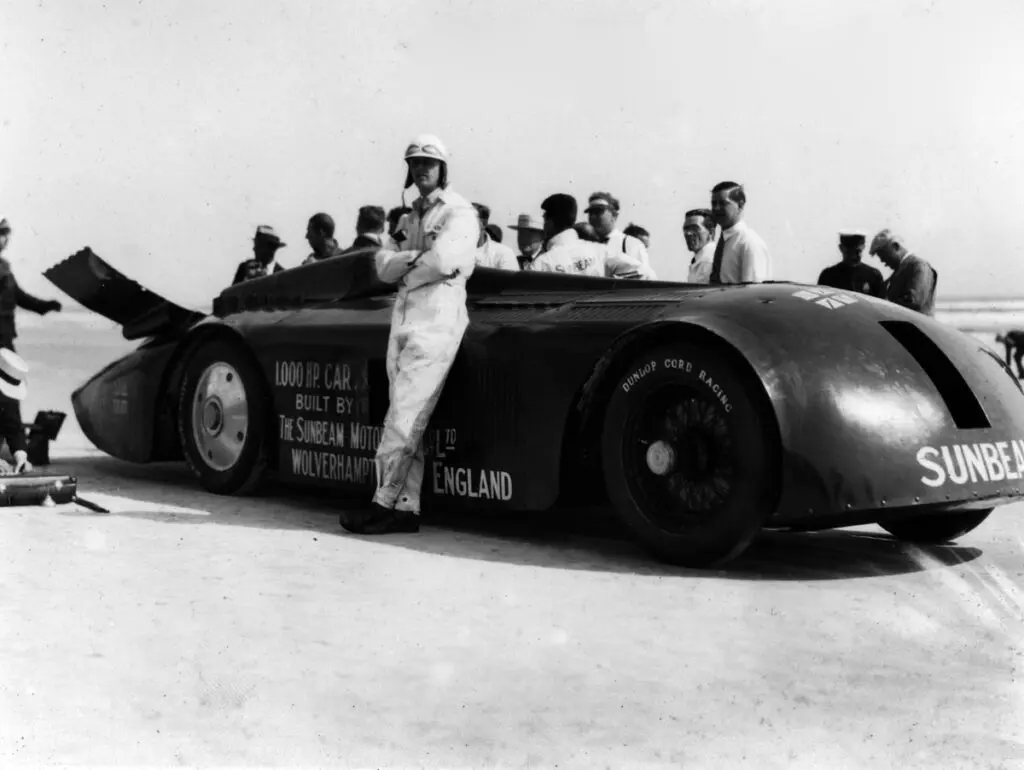

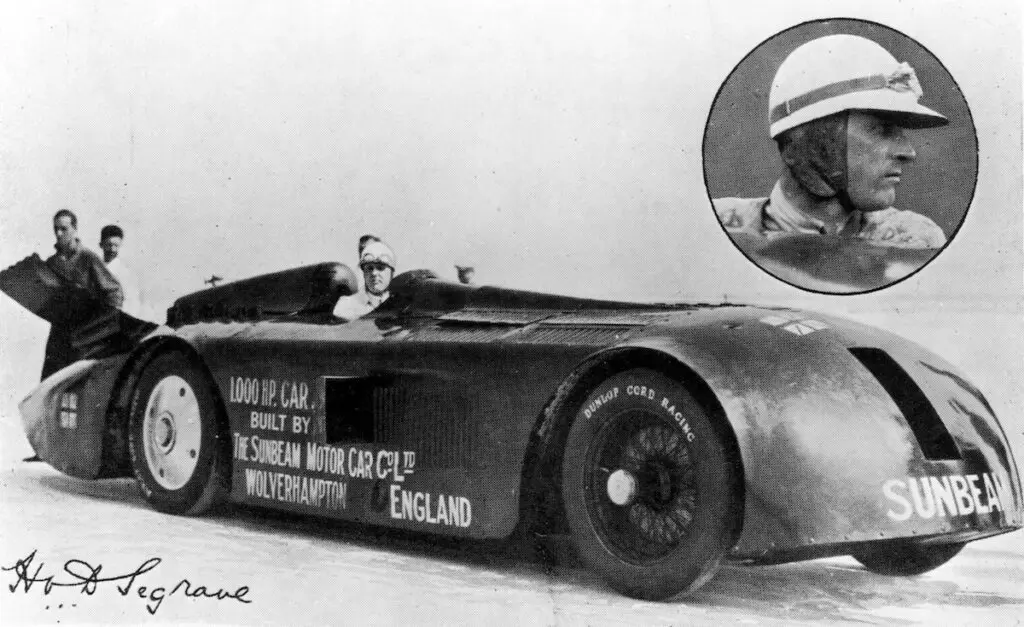

But those naysayers didn’t factor the skill and determination of three extraordinary men, supported by a host of British engineering companies who flocked to support this home-grown motoring leviathan. Segrave was the face of the project – the driver with a chiselled jawline whose innate charm hid a ruthless determination to succeed. This included shouldering the logistical challenges of the project, pulling together the financial support of sponsors and finding an appropriate venue for the attempt. As biographer Cyril Posthumus wrote, he was: “Segrave the diplomat, the negotiator, the organiser.”

Then there was Sunbeam’s powerhouse, chief engineer and designer Louis Coatalen. Together, he and Segrave had already achieved a motoring milestone by winning the 1923 French Grand Prix in a Sunbeam, the first time a British driver had achieved such a position in a British car. Then, in March 1926, Segrave took the Land Speed Record driving at 152.33mph over the mile in another Sunbeam, a red 4.0-litre Tiger nicknamed Ladybird – but within six weeks the title had been taken by John Parry-Thomas driving Babs on Pendine Sands at close to 170mph. Segrave immediately telephoned Coatalen, who was in Paris, to discuss their response. “I shall be back in London tomorrow,” the latter responded. “Come and see me then.”

The pair reasoned that they needed to smash the existing record, not simply break it. Segrave wanted 200mph, and for Coatalen that meant brute force. Said Henry: “He [Coatalen] reasoned that, if it had to be power, then power he would use – more than any other.”

That power came from two huge Sunbeam Matabele engines that were in storage at the factory, having already led rather eventful lives. Built in 1918, but surplus to requirements when World War One ended, in 1920 they’d been two of the four engines that propelled the Maple Leaf V, a 39ft single-step hydroplane, in the Harmsworth Trophy international powerboat race off the Isle of Wight – the British challenger to dominant American competitor Gar Wood.

The following year, transplanted into the lighter, 34ft, plywood Maple Leaf VII, the engines ran again in the same event, this time held in Detroit. In the first heat, having led off the line at a reported 70mph, the fragile hull gave way and the boat sunk, leaving Wood to win yet again. The waterlogged motors were recovered, returned to the UK and sat there – until Coatalen and Segrave saw their terrestrial potential.

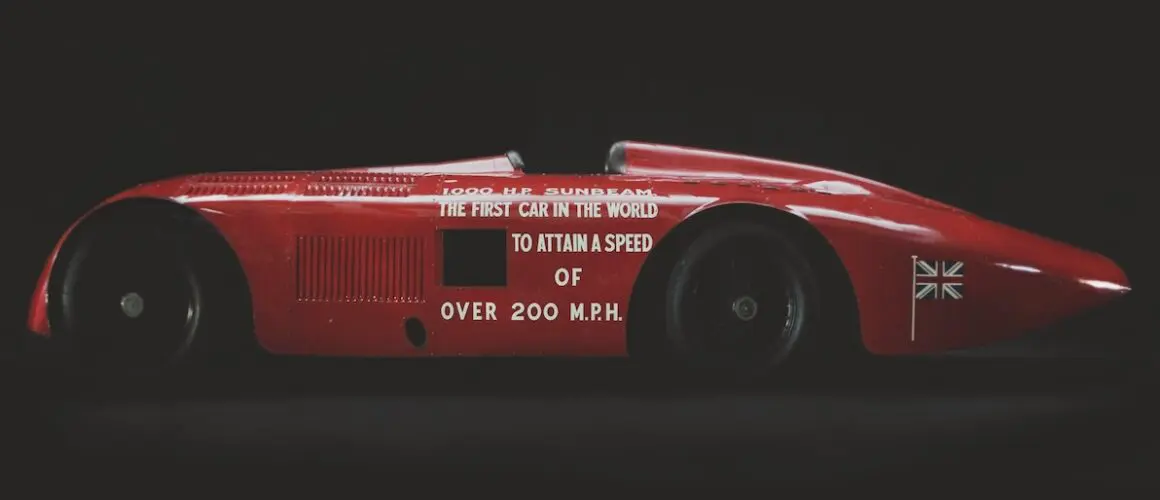

Each was a vast, 22.5-litre V12 with double overhead camshafts and 48 valves, putting out 435hp at 2000rpm. Coatalen quickly created a concept: one engine in the forward position, driving back in the typical manner towards a custom-made three-speed gearbox, and the other placed behind the cockpit, driving forwards through a countershaft, with chain sprockets on either side powering the rear wheels. The all-enveloping body was designed to be like an upturned boat, and had a flat steel undertray, described at the time as being in case of “a tyre coming off or any such untoward accident; serious consequences will be avoided by the fact that the car will slide along”, but almost certainly providing aerodynamic benefits.

The basic design achieved, Coatalen passed the responsibility for creating the machine – its name rounded up to the press-friendly Sunbeam 1000hp – to the third member of the trio: the firm’s chief engineer Captain JA ‘Jack’ Irving. Working at the Moorfield facility, he quickly put Coatalen’s concept together, combining a chassis frame made by John Thompson Motor Pressings, steel forgings produced by Vickers, specially built Hartford shock absorbers and a Dewandre Vacuum servo-braking system.

Various issues were noted and overcome: wind-tunnel tests of a model showed a tendency for the car’s rear to lift at speed, which was overcome by a modified tail design, while the drive chains became almost red hot during trials. Finally, on March 2, 1927 – less than four months after construction started on November 11, 1926 – the car, along with 18 crates of spares, was loaded on the Berengaria liner in Southampton, bound for New York.

Just one day out into the Atlantic, they received the news that Parry-Thomas had been killed at Pendine when Babs overturned – prompting yet more discussion about the exposed chain drive on the 1000hp, but not dulling the team’s enthusiasm. When the car, driver and Sunbeam entourage finally arrived in Florida, they were met with a flurry of press, escorted by the local police and feted by Daytona Beach dignitaries.

The huge red machine rolled out for its first test run on March 21 in front of an estimated 10,000 spectators, and it quickly gained the rather unfortunate nickname of The Slug. At this point, it had driven just 300 yards or so at Moorfield, so Segrave’s first run was kept to a conservative 110mph. This identified a number of issues, including that the steering was too low geared and the rear engine was overheating. Those problems remedied, three days later he took another run, this time allowing the huge engines to run freely and speed to build.

Now, other unforeseen issues became evident: the wind pressure forced oil-misted, sandy air into the cockpit, buffeting Segrave to the point that his goggles and helmet were fluttering around his face. Then, as he stamped on the brake pedal at the end of the run, there was a brief reduction in speed followed by a total failure of the system. The car finally slid to a halt 2.5 miles later. The aluminium brake shoes in the rear drums had melted, rendering them next to useless. Most annoying for Segrave, the test was also an opportunity to trial the official AAA timing gear for the first time, and it proved to be extremely inaccurate, variously recording speeds between 166mph and 280mph – the former being issued as the official time. This was disappointingly low.

Later, it was found that spectators had trampled the wires, but Segrave was not told, so the team decided to lower the gear ratios for safety. This, in addition to changes in the wind cowling and the addition of linings to the brake shoes, convinced the team that they were ready to make an attempt on the 200mph target.

At precisely 9:30am on March 29, the huge beast rolled out onto the Daytona sands, where the waiting press snapped photographs of car and driver. Using compressed air, the mechanics started the rear engine, which in turn fired up the front one. Segrave rolled out onto the track, delineated with 12ft poles marked with red and black diagonal stripes, and began his run.

At first, all went well. But just as he reached the start of the course, a gust of wind caught the car’s vast flanks, pushing him off line. It took him nearly a mile and a half to correct the swerve. Pushing hard at the peak 2200rpm, he flashed through the measured mile, 1km and 5km sections, only to be pushed off course once again, this time hitting a line of marker poles and skidding over 400 yards before Segrave once again brought the monster back under control, lifted his foot from the accelerator and pressed the brake. Very little happened.

He realised that the beach was running out fast, and unless he acted quickly, he’d soon be entering the Halifax River or crashing into sandbanks at speed – neither of which offered much hope for his survival. He took a third option, and pulled the Sunbeam left into the sea, steering for the shallows of around 18in deep.

To his great relief the plan worked, and the car slowed enough for him to drive under control back to the tyre depot at the north end of the beach. New wheels were quickly fitted, before he started on the return leg, which proved to be much less eventful than the first. After flashing through the timed area and slowing the car, he circled back to the AAA timing stand, where he was met with beaming smiles. He’d done it: an average of 203.79mph for the mile made him the fastest man on the planet.

The press, in both America and Great Britain, went wild. Sunbeam proudly produced a booklet entitled The Greatest Motoring Achievement Ever Recorded, The Motor speculated that “Major Segrave’s record will probably stand for a long time”, and The Autocar called it a “wonderful combination of man and machine”.

Unfortunately for Segrave, The Motor was wrong. Within a year, Malcolm Campbell had bettered his record, driving Blue Bird to 206.956mph, and then, in April 1928, American Ray Keech pushed it up to 207.552mph. Undaunted, Segrave linked back up with Irving and tried again in 1929, smashing the record in the Golden Arrow at 231.446mph and gaining a knighthood in the process.

The 1000hp car was packed away and, for a time, forgotten. After the war, it was included in various motoring cavalcades then, in 1958, the Montagu Motor Museum at Beaulieu received the Sunbeam on loan from the Rootes Group. It was described thus: “Single-seat aerodynamic, with cowled headrest. Red. Condition indifferent. Tyres do not hold air and pistons missing from forward engine. Truck tyres fitted.”

It toured Goodwood in 1960 and Oulton Park in ’62 as a static display, then in ’70 it was purchased by the museum. Other than a repaint in ’72, maintenance and the odd excursion on display to various shows, the old car has remained relatively untouched – until last year, when its refurbishment began. This was the result of a conversation overheard by Martin Braybrook, MD of multiple championship-winning motor sport team Brookspeed Automotive and keen Beaulieu supporter.

“I was standing by the car at the National Motor Museum, and heard Jon and Patrick talking about how great it would be to hear it run again,” Martin tells me. “I’ve raced many times at Daytona, and just thought ‘why not?’, so I said as much.” Jon Murden, museum CEO, and Patrick Collins, curator of vehicles and research, loved the idea; the concept was born.

“Getting the 1000hp running again fitted in well with our plans,” Jon adds. “We’re at the start of a programme that will transform the museum – the physical building and the way we encourage people to interact with our exhibits. Bringing the phenomenal Sunbeam 1000hp back to life will help raise funds, as well as introduce a whole new generation to an extraordinary feat of engineering and part of our national heritage.”

Not content with just repairing the engines, the museum made the decision to return the car to fully running condition – and aims to send it back to Daytona Beach on the 100th anniversary of its Land Speed Record run, in March 2027, raising the possibility of US donations.

“Segrave was born in Baltimore and had an American mother, so was a true transatlantic hero,” Jon explains. “We’d obviously love to gain backers in the US who could support this amazing piece of Anglo-American history.”

Bringing this car back to a driveable state requires not only engineering work, but also a very keen focus on maintaining the history of this nationally important artefact – a fine balancing act that’s been entrusted to museum senior engineer Ian Stanfield, known as ‘Stan’.

“The rear engine has already been stripped, and we’ve tried to keep everything as original as possible,” he tells me. “Parts that weaken over time have been replaced – valve springs, piston rings, brake linings and the like – and other parts that were either missing or damaged, but nothing else. Terry Formhalls kindly offered the support of Formhalls Vintage & Racing, and white-metalled all the surfaces for free. Mostly it’s just been hours and hours of cleaning.”

One of the most sensitive parts of the restoration was the chassis. This needed to be inspected for cracks but its historical integrity maintained. Stan pressure-washed before soda-blasting it – a less aggressive process than the more traditional shot-blasting. This care paid off: original makers’ marks were found, and will be preserved under a clear-coat of Trimite paint. Next, the unpainted parts will be cleaned with a laser process, and other components will be made from scratch. The compressed-air starting mechanism, unique to this engine, had been lost over time, and another is now being recreated with the help of a distributor borrowed from the Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust.

Other fascinating links back to the car’s construction were found. A 1921 shilling and an adjustable spanner were discovered embedded in thick oil on the suspension, and a screwdriver turned up in the oil tank. “It’s the first 200mph ’driver,” laughs Stan. “We cleaned out the tank, where the oil had solidified, and after shaking, the vintage tool eventually tipped out.”

As the Sunbeam slowly reveals its secrets, the 100-year-old engineering has struck all involved. “Everything is well made,” Stan says. “The skills back then were phenomenal.” Martin Braybrook agrees: “Given what equipment they had available, it is all very impressive. The wheel bearings are massive, but they look like they could have been made today.”

The team have their work cut out. The plan is to have the car running by 2026, ready to tour the UK, Europe and the US, with opportunities for schools and colleges to get involved with STEM activities. Then, on March 29, 2027, 100 years after Segrave’s run, it may once again thunder down Daytona Beach. Exactly how fast is yet to be decided, but a repeat of the 203mph record is out of the question, to preserve both the driver and this piece of motoring heritage – although the experience of hearing this leviathan roar again will be one not to miss.

And then what? The museum also owns Segrave’s 1929 Golden Arrow record car. Is this pencilled in as the next major project? Jon Murden is being careful not to over-promise.

“One step at a time,” he says. “The museum has just reached its 50-year anniversary, and we must raise millions to transform it for its next half century. We want to improve our spaces, equipment and interpretation for youngsters, as well as upgrade facilities for the conservation and restoration of our display vehicles.

“We also plan to open up our stored collections of more than 1.9 million items of automobilia, and make them accessible for everyone. The world of motoring is rapidly changing, and we must keep pace to tell its story. Mind you, imagining the Golden Arrow running next to the other cars is a tempting prospect…”

Donations for the Sunbeam 1000hp Restoration Campaign can be made online. Sponsors and corporate donors who’d like to be associated with it are urged to email [email protected].

This article is dedicated to Terry Formhalls, who died the week it was written.