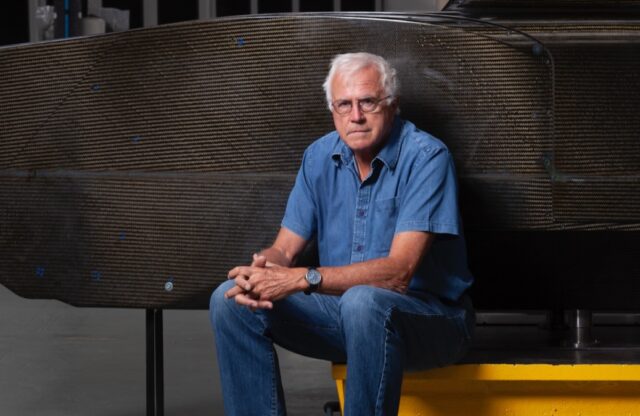

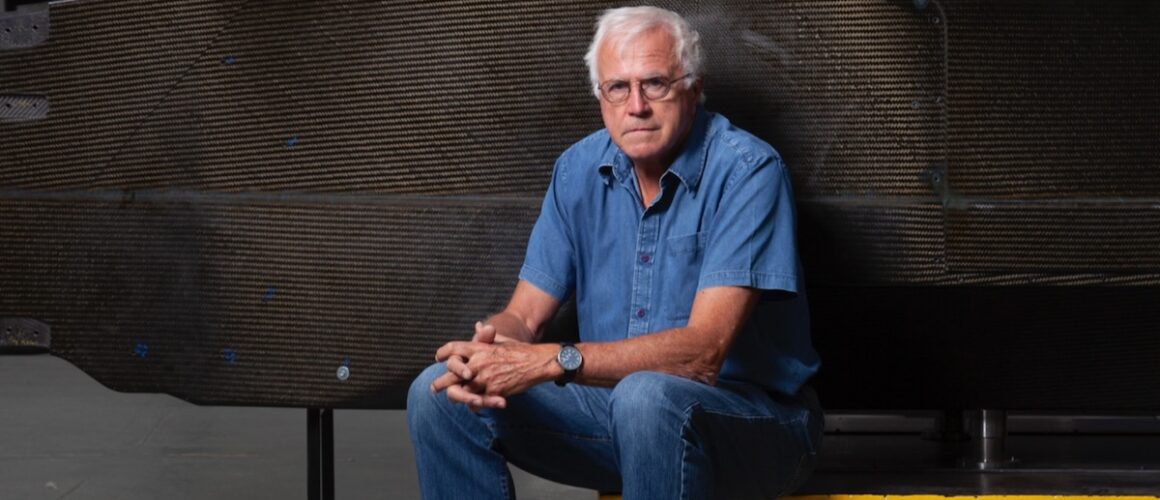

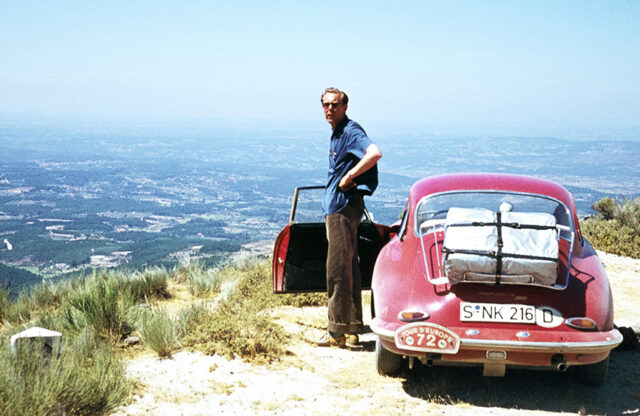

Sad news on Thursday November 6, 2025, writes designer Peter Stevens. At the age of 79, Peter Wright has died. Peter was a typical Renaissance Man; he was eternally curious, a fabulous communicator, a logical thinker and a great believer in returning to first principles.

He was never afraid to ask others for their opinion, and he was always ready to credit them for their contributions. He will always be credited as being the ‘father of ground effect’ aerodynamics, something he always denied. Working with the remarkable engineer Tony Rudd at BRM, the two were both fascinated by the principles of flight. They suspected that there should be a way of harnessing those principles to prevent race cars from tending to lift at speed, and maybe even create some form of downforce. BRM’s then current driver John Surtees thought that Rudd and Wright were wasting valuable resources on ‘that nonsense’ and put a stop to it.

Shortly after this, both men moved to Lotus where, in 1977 Colin Chapman gave them the freedom to pursue this line of research. Peter suggested that they use the Imperial College ‘Campbell’ wind tunnel because it had a rolling-road floor, essential for developing air flow beneath a car. With input from race car designer Ralph Bellamy, pattern maker Charlie Prior and Frank Irvine from the Imperial College Aeronautics Department, they surprised themselves with their results.

From this work came the Lotus 78 and 79. It was in the Lotus 79 that Mario Andretti won the Formula 1 World Championship title in 1978. Peter did later say that it was ground effect that ruined Formula 1. He quickly realised that the underside of the car gave huge downforce if the car’s side pods were sealed to the ground by sliding side skirts. From this breakthrough came his idea that if you could stabilise a race car, so that it didn’t get deflected by bumps, the ground effect would work even better. From this came active suspension.

Working with aerodynamicist, code writer, suspension designer and sandwich eater John Davis, Lotus developed a unique suspension system that was fitted to numerous road cars for curious manufacturers. There was a reluctance for any of them to take up the system, although General Motors bought Lotus in the hope that it became a saleable idea. I suspect that the natural conservatism of the industry didn’t trust the technology – unlike Ayrton Senna, who loved the breadth of handling possibilities the system allowed.

During this period Peter Wright was never quite sure what his role was within Group Lotus. It was often only after being introduced to visitors by Chapman that he knew what it was on that particular day. Whilst I was at Lotus, Peter was engineering director, with responsibility for both Lotus products and customer’s cars. He could take a hard line with new owner General Motors. He was involved in the development of the Lotus Omega and its UK equivalent, the Lotus Carlton, and he was frequently frustrated by GM Germany’s belief that the car was perfect and there was nothing that Lotus could do to improve it.

When his engine team found that the cylinder-head castings were full of sand, and that GM’s vice-president of design, Chuck Jordan, was looking after the car’s design, he brought the project back to Lotus at Hethel. He threw away the dead albatross on the boot lid that was supposed to be a rear wing, and sent me off to the MIRA wind tunnel to do a proper job.

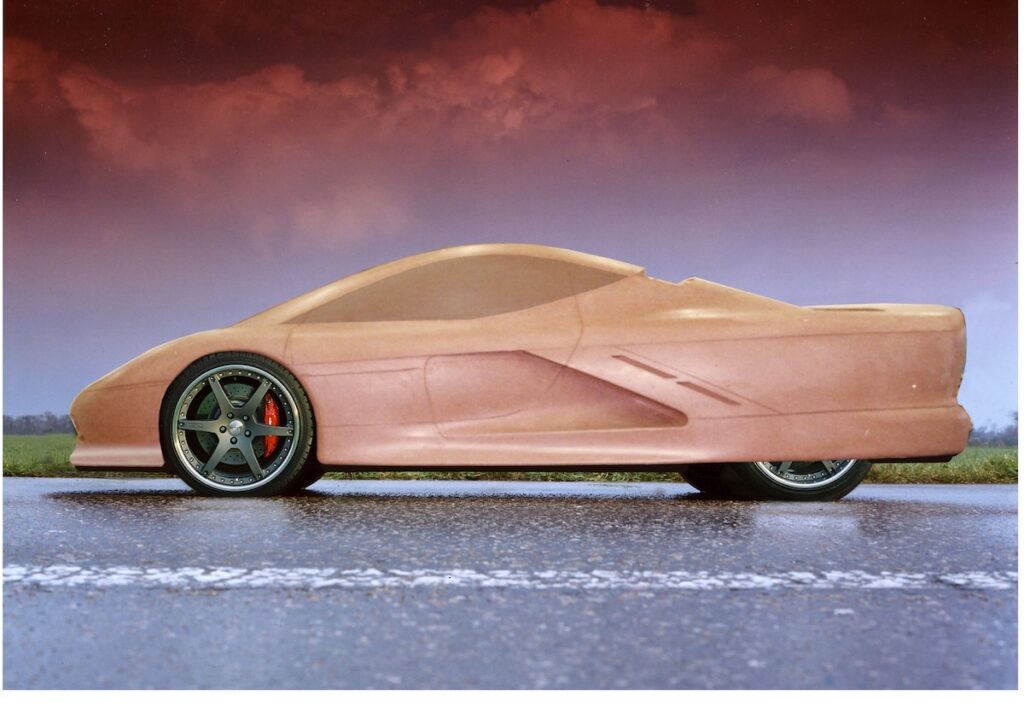

In 1989 Peter also proposed to John Davis and me a hybrid sports car concept that he had in mind, the B2. His brief was very simple: “I am giving you 300bhp and I want to do 200mph. What should it look like?” He believed strongly that hybrid or electric was the future, just not like we are doing it now.

After the tragic death of Senna at Imola, Peter was invited by the FIA to propose a scientific approach to reducing injuries or worse in motor racing. He took his highly analytic approach to solving problems and applied it to motor sport safety, the result of which is what we still see today. This was a huge contribution to saving lives. His autobiography, How did I get here?, is written in his light but easily understood prose that was always a delight. And he was a passionate soft-fruit farmer, pilot and friend.