Incredibly, the XK120 was supposed to score Jaguar founder Sir William Lyons a quick hit before moving on. That’s because the saloon range intended to receive his new XK engine wasn’t going to be ready in time for the 1948 Earls Court Motor Show.

Yet response to the new model, dubbed “the fastest production car in the world”, was overwhelming – so much so that earlier plans to build a mere 200 were quickly shelved. Revisions soon followed: a Fixed-Head Coupé (FHC) joined the Open Two-Seater (OTS) in 1951, marked only for export, making right-hand-drive cars special commission only (and extremely rare to boot).

Power output went up that year, too: SE cars now produced 190bhp (up from 160bhp), and 210bhp could be had from the optional ‘C-type’ head. A final bodystyle joined the line-up in 1953; the Drophead Coupé (DHC), complete with wind-up windows and the FHC’s walnut dash, along with a proper hood. While the XK120’s story came to an end in 1954 after just over 12,000 cars were built, it had set an astounding precedent.

The XK140 took what Jaguar had learned with the XK120 and made the car an even more attractive proposition for buyers. There was more room in the cabin because the engine, enlarged and more powerful, had moved forward. Rack-and-pinion steering featured for the first time, telescopic dampers replaced the XK120’s lever arms and a repositioned roofline allowed for two rear seats to be fitted for the first time.

Racing experience was fed directly into the XK150 of 1957, which not only looked different but also went and stopped far harder than the previous two generations of XK. Styling tweaks modernised the shape for the late 1950s; a single-piece windscreen, wider bonnet and shallower curved wings disguised four-wheel disc brakes, derived from the Dunlop units on the C-type racer.

The final 3.8-litre evolution of the XK150 was built in direct response to the small-block V8 competition in North America. It produced 220bhp as standard, with 265bhp on tap if the S specification was ticked. Exactly 9382 cars later, as the last XK150s left the line, a new model was ready to take its place: the E-type. Without the trailblazing export drive of the XK series, that car might never have happened.

ENGINE AND GEARBOX

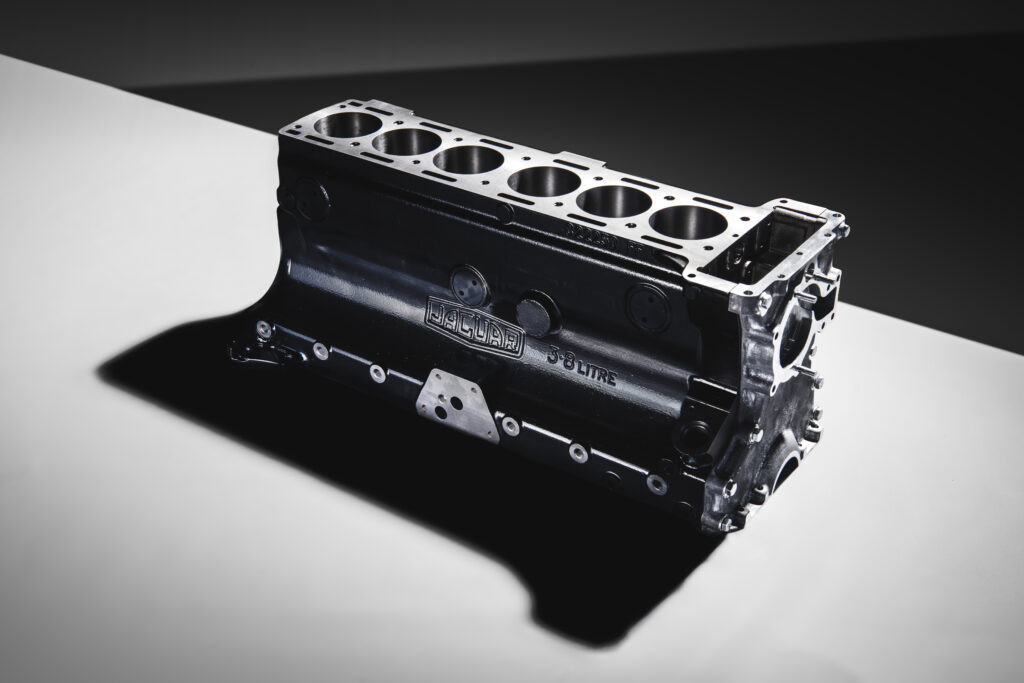

“The heart of any XK model is the XK motor,” says Harry Rochez, assistant manager for Twyford Moors Classic Cars. “Check the engine and block numbers to see if it’s original to the car; so many XK units were built, it’s not unusual to see a later engine in an earlier model. It’s down to personal taste, but that should be reflected in the value of the car. Ask to see its Jaguar Heritage Certificate if it has one; this will tell you the original engine number, among other things.”

Harry continues: “Overall the engines are very robust, but the timing-chain tensioners can become lazy, which will give a rattling chain, and valve gear can become noisy. Rebuilds are quite common, however, and not the end of the world.”

Don’t be put off if an electric cooling fan has been retro fitted; all XKs tend to get hot in traffic because they weren’t built to be driven in modern jams. Modifications such as these don’t detract from the value, either. “People generally buy XKs to use,” says Harry.

The non-synchronised Moss gearboxes, used throughout production, are the XK’s Achilles’ heel. In Harry’s words: “They’re a slow ’box in a fast car; you need to be patient between ratios, there is no synchromesh on first, and second tends to wear out, so you need to double declutch. They can be rebuilt, but there are no new parts, and it gets quite expensive. The XK140s and XK150s had overdrive as an option; it makes them quite long-legged, but the units are temperamental and very sensitive to oil levels. They have an electrically operated solenoid that needs adjusting properly.”

Better gearboxes are an option; many specialists plump for the W50 series unit as used in the Toyota Celica/Supra: “Five-speed gearbox conversions are one of the most popular conversions in the XK world,” says Harry. “We’ve done thousands of swaps over the years.”

SUSPENSION AND BRAKES

XK120s and XK140s had drum brakes all round; it was with the XK150 that Dunlop disc brakes were fitted. The correct adjustment and maintenance are crucial on the earlier cars, and the units need warming up before you set off to drive. XKs are quick vehicles, even by modern standards; many XK120s and XK140s have since been upgraded to front discs.

Don’t be put off by an XK150 with a poor handbrake. “The arrangement for the handbrake on the XK150 is atrocious,” says Harry. “You can get them to work better, but it’s a case of ‘adjust, adjust, adjust’: it’s something that few people manage to do.” Twyford Moors is currently working on a conversion kit.

The XK120 used lever-arm dampers at the rear, which tend to leak and are expensive to rebuild; XK140s and XK150s used telescopic units all round, which are far stronger. Ball-joints and bushes can wear out, ruining the handling. XK120s have a steering box, which is costly to rebuild if there’s play, but so is upgrading the relatively narrow chassis to rack and pinion, as seen in the XK140 and XK150.

“You have to alter the chassis and fit a different radiator,” says Harry. “It’s a lot of work; we tend to do it at restoration stage.”

BODYWORK AND INTERIOR

“There’s nothing we can’t rebuild on an XK, no matter how bad it’s got. There’s not a single panel that isn’t made or can’t be made,” explains Harry.

A crucial rot point is where the rear wings are bolted on. Also, earlier doors have wooden frames with aluminium skins; the frames can rot, pushing the doors out of alignment. Steel equivalents are available. Although front suspension mounts can corrode, specialists such as Twyford Moors have jigs that can sort this.

Check for panel gaps and how they fit together; badly fitted panels can ruin the look of the car, especially where the wings meet the doors. Aligning things properly takes time and costs money. This model’s bodies were mounted on spacers, and no two examples were the same.

If looking at more expensive cars, check that they have had a body-off restoration, with time spent sorting those panel gaps. “People in that market expect better than what the factory managed at the time,” says Harry. However, if a car is otherwise sound, it can make for a cheaper XK that’s a perfect ‘driver’.

Carpets and seats wear, and can be replaced, yet switches and hood frames can be hard to come by. Frames are made but have to be fettled to fit a specific car.

WHICH TO BUY

Harry says: “For me, it would be an XK150 FHC. I love the shape and practicality; I can get my children in the back. Of all the cars, they offer incredible value for money. XK120s have their own charm, but you have to be conscious of what you’re driving; an XK140 or XK150 could be used on the M25 without thinking about it.” Any factory-built right-hand-drive XK will fetch a premium over an equivalent left-hand-drive car; more than 75 percent of XK production went overseas. Any conversion work needs to be declared.

OTS cars are the least practical but have the prettiest shape. “They’re popular with people who want a car for high days and holidays,” says Harry, “but they’re not much good for touring, and you need a scout troop to put the hood down. They also have screw-in side screens instead of winding windows. DHCs are the most popular XK, because they’re a fair compromise between the visual appeal of an OTS/ Roadster and the FHC’s innate practicality.”

He continues: “DHCs have wind-up windows, a walnut dash and a hood that can be raised and lowered by one person. We find XK140 DHCs are very popular. FHCs have a solid roof, making them less valuable, but there are exceptions; only 195 XK120 FHCs were made in right-hand drive, and they are incredibly sought after.”

WHAT TO PAY

1959 XK150 3.4S FHC, UK

Fair: £41,400

Good: £54,200

Excellent: £69,400

Concours: £103,000

1959 XK150 3.4S FHC, US

Fair: $54,600

Good: $74,500

Excellent: $124,000

Concours: $157,000

SPECIFICATIONS

3.8-litre inline-six (XK150 3.8S FHC)

Power: 265bhp

Top speed: 136mph

0-60mph: 7.6 seconds

Economy: 17mpg